TRAILBLAZER

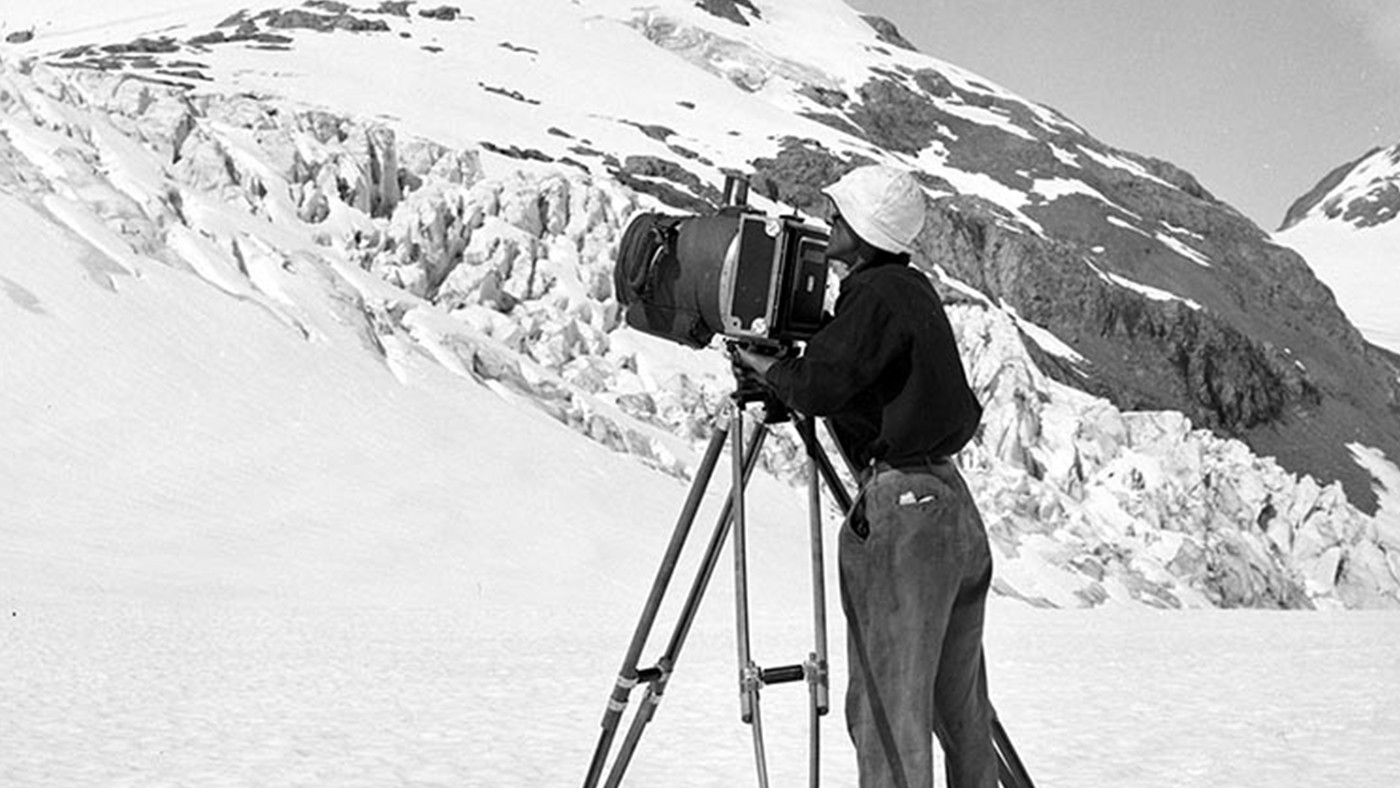

Mountaineer Bradford Washburn didn’t just summit some of Alaska’s most fearsome peaks—he also photographed them, to stunning effectHanging out of a plane at 15,000 feet, clad in a makeshift head-to-toe sheepskin suit and fur-lined headgear with a mitten on one hand and a glove on the other so that he could operate his camera, intrepid mountaineer and outdoor photographer Bradford Washburn risked his life to get the perfect shot. His preferred large-format camera weighed 53 pounds and required Washburn to have the aircraft’s passenger door removed before lashing himself to the fuselage so that he wouldn’t fall out as he shouted and signaled directions for the pilot over the roar of the engine and the screaming wind (it helped that Washburn was a capable aviator himself). Since the planes always shook violently, getting crisp photos was the biggest challenge of all. The solution? Washburn devised a way of securing his camera in a crisscross of mesh straps, where it sat suspended like a giant spider in its web. Then he tuned into the rhythms of the juddering aircraft, timing his snaps, he later explained, to the crest of the “bounce.”

In the 1930s and ’40s, these were the kind of white-knuckle flights required to capture North America’s wildest mountains on film. And there was no one who captured them better than Washburn.

Before he got serious about photography, Washburn, who passed away in 2007 four years shy of his 100th birthday, distinguished himself as one of the world’s best climbers. Over the course of his long career, he scaled many high places where no one had set foot before, and inspired generations of mountaineers to follow in his tracks. His playgrounds of choice were Alaska and the Yukon, where, among other accomplishments, he pulled off first ascents of no fewer than five remote peaks between 1933 and 1953. The energetic, 145-pound Boston native made 20,310-foot Denali a focus of his alpine obsessions. Washburn led the third party ever to climb North America’s tallest peak—called Mount McKinley in his era—and established the route that remains, some 70 years later, the most popular way up. Understandably, the man is a legend among the ice-ax set. But Washburn’s legacy doesn’t end there. In the process of conquering and surveying great mountains, he left behind some of the most breathtaking landscape photographs of the 20th century, not to mention the first aerial images of Denali—images that any armchair-bound flatlander can appreciate.

The son of an Episcopalian minister and a member of an old Massachusetts family, Washburn got his first camera at age 10 and taught himself to take pictures. Though blue-blooded, his parents were not wealthy. A rich uncle paid his way through Groton, and his mother fretted that her son would decide to make a career of guiding. She needn’t have. Washburn took a job at Harvard, where he taught at the Institute for Geographical Exploration. In 1938, he became the director of a dusty, little-known Boston museum. He retired some 40 years later, having transformed it into the city’s renowned Museum of Science.

One thing these two jobs had in common is that they allowed Washburn an Indiana Jones–worthy lifestyle—a professor during the school year, and a high-risk, high-altitude climber in the summer months. It was during those weeks between classes that he developed his signature photography style, a fast-and-light approach that took full advantage of Alaska’s legendary bush pilots. To get unique shots, he tested the limits of this fearless bunch, persuading them to land at altitudes they’d never attempted before, in the process flying in everything from the building materials for a one-room staging cabin to a team of yapping sled dogs.

And although some of his images approach abstraction, Washburn’s eye never strayed far from the cold, hard facts of the rock. His iconic arrangements of rock, snow, light, and shadow are less emotional and more frank than the black-and-white photography of Ansel Adams, whose name comes up often in discussions of Washburn’s work. The two enjoyed a respectful friendship, even if Washburn claimed never to have studied the master’s work too closely. Stubbornly utilitarian, Washburn was self-taught and had no problem touting his achievements in exploration and science, while all but ignoring the artistic dimensions of his work. He used photos—in lectures and magazine articles, but not by selling prints—to raise expedition funding. And crucially, he studied his own razor-sharp prints to figure out the best path to the summit.

As Washburn became the world authority on Alaskan mountaineering, interesting commissions came his way. One involved winter-testing World War II gear, which he did while serving on an elite government consulting team that included polar explorers Sir Hubert Wilkins and Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Another came from a Hollywood studio, which hired him to lead a footage-gathering expedition for the 1950 film The White Tower. As biographer David Roberts has pointed out, Washburn led every expedition he went on. His wife, Barbara, sometimes joined him—becoming the first woman to climb Denali and several other Alaskan peaks.

And though he was a meticulous planner, Washburn had his share of close calls. Narrowest of all was the Mount Lucania expedition that he and partner Bob Bates pulled off in 1937—a mind-boggling traverse of unknown lands that required them to bushwhack 100 miles back to civilization, nearly starving and drowning in the process. Writing 70 years later, Roberts called it “probably the single bravest and most unlikely mountaineering feat ever accomplished in the Far North.”

Washburn, who carried a smaller camera while on foot, wasn’t documenting the latter part of that journey; he was trying to survive it. Earlier, though, on top of Lucania, he took a shoelace-triggered snapshot of himself and Bates. Beautifully composed, full of dizzy energy, the photo swells with a top-of-the-world sense of triumph. In addition to his other photo credits, Washburn can lay claim to one of the original summit selfies.

- Images courtesy of the Museum of Science, Boston