Setting Sail

A look at the heritage and sport of the Hawaiian canoe, with the local legends—and new Polo models—who are carrying on the traditionIn March of 1975, something special happened on the beaches of Hawaii’s Kāne‘ohe Bay of Oahu: a traditionally made Hawaiian voyaging canoe was set out from the shore for the first time in more than 400 years.

Historical documents show that in centuries past, these boats would have dotted the Hawaiian shores by the hundreds or even thousands. Now, you would be lucky to see a few—if any at all— on most Hawaiian beaches, as the ancient tradition of Polynesian canoe sailing was almost lost to history in the 20th century. Thanks to nonprofits like the Polynesian Voyaging Society, though, and dedicated students who are reclaiming the nearly lost knowledge of instrument-free navigation, traditional Hawaiian sailing is seeing a renaissance in the modern era.

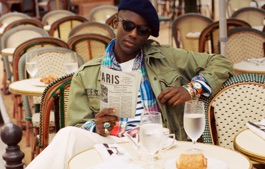

For Polo’s Spring collection of colorful, beach-ready sportswear, we headed to Oahu and spoke with two of the modern-day sailors—Austin Kino and Hopena Pokipala—who are keeping the tradition alive as they showed us the ropes and modeled the season’s new styles.

AUSTIN KINO

Born and raised on the south shore of Oahu, Austin Kino has had a lifelong relationship with the ocean through surfing, fishing, paddling canoes, and more. In high school, he decided to add something new—traditional Polynesian sailing. Now, at 32, he’s one of the most passionate advocates and educators on Hawaii, regularly sailing on monthlong no-instrument voyages.

You’re an accomplished sailor and teacher of traditional Polynesian sailing. Tell me a bit about that.

I sail and volunteer for an organization called the Polynesian Voyaging Society, which is dedicated to Hawaii's history of non-instrument celestial navigation, from the building of traditional double-hulled sailing vessels to learning how to navigate them without any modern instruments—just using what is around you in nature.

I also run an education program, called Huli, that takes kids and community members out on these canoes to let them experience a pastime that has been a big part of Hawaii’s history.

For someone who knows nothing about this kind of sailing, what are the basics?

There are two main things to focus on—one is bearing, understanding which direction you’re actually facing. Sailors had a concept of east and west based on the sun, and they had a concept of north and south based on certain stars. The second is speed. Instead of having a tool to read how fast they were traveling, they would observe something like how fast the bubbles of white water and the ocean would pass their vessel. So that’s what you’re always paying attention to—what direction are we going in, and how fast are we getting there?

Can you talk a bit about the design of the boats?

One primary feature of all Polynesian canoes was the addition of an outrigger. As opposed to a dugout canoe that balances by its weight, Polynesian canoes always had balance on the ocean because of an additional flotation outrigger that was lashed onto it. That’s the primary trait, found throughout Tahiti and New Zealand.

There are smaller canoes for what we’d call coastal sailing. Those would be anywhere from, say, 10 to 30 feet, and their main goal is to just transport people around the island, and they can sail up to 10 people safely. That’s what we used on the Polo shoot. The next tier is the deep-sea voyaging canoes. These typically are double-hulled—so instead of an outrigger, you have two hulls lashed together. And those canoes, like the ones we use at the Polynesian Voyaging Society, can be upwards of 60 to 70 feet long and have a carrying capacity of anywhere from 15 to 20 people, plus all their cargo. Those do long voyages.

What are some of the most significant voyages that you’ve taken? Are there any that were especially meaningful, or difficult, or that you’re extra proud of?

It was before my time, but the first voyage that happened on a sailing vessel like this in modern times was in 1976. I remember seeing it in National Geographic—the first Hawaiian voyaging canoe, called Hōkūleʻa, made it from Hawaii to Tahiti using non-instrument navigation. That was something that hadn’t been done, they think, in six or seven centuries.

I grew up learning about that. And then as a sailor, I was asked to be a part of a navigation team for the first leg of a worldwide voyage that the Polynesian Voyaging Society was doing, using the Hōkūleʻa. That first leg was from Hawaii to Tahiti. It’s called the “road of our ancestors,” the trip between these two places, and to travel it myself, on that vessel … that was really special.

It seems like teaching is a huge value in the sailing community. You and Hopena were so welcoming in showing sailing to us, and you both have education efforts to pass on your knowledge.

You can be a master of the universe and know every trick in the book, but unless you have a student, your craft will eventually die. So guys like myself and Hopena, now we understand that scarcity and the need to teach and to take people out on the water. The knowledge that we were given was given freely. All we had to do was put in our work and our time and our commitment. That also means that we need to have the capacity to give it freely ourselves. That’s a huge value that we all share.

And it’s not just for kids, too. The canoes are relatively safe compared to, let’s say, a surfboard. So we’re getting a chance to take out families or maybe some older members of our community—who because they weren’t surfers, or weren’t crazy about boats, have never really been out in the water—and giving them the opportunity to see the land that they grew up in, from the ocean.

That journey from Hawaii to Tahiti—that’s a long distance. When you did that voyage yourself, how long did it take? And how did it feel, traveling that historic path?

It’s a distance of roughly 3,000 miles, and with the trade winds of the Pacific, we generally sail around five knots. So it takes about 28 days to a month.

On that first voyage that I was on, we hit a storm that pushed us through this area called the doldrums, where you don’t usually get a lot of wind. So we made it a little bit faster, in 23 or 24 days. But normally, like, you’ll sail really well until about 5 degrees north, and then the winds kind of shut off, and you just drift through part of the planet until you reach the other side of the equator, 3 or 4 degrees south, and then you get the trade winds from the south.

There was one night where I was off watch and just lying down on the deck, looking up. And we were just flying—we had so much wind, and the guys are steering, and it just kind of hit me, all of a sudden. I couldn’t believe that people before me were brave enough to do this, not knowing where they were going. It really got me to appreciate, in that moment, the level of experience that these ocean goers had, and how that’s a part of our history.

I felt like I had gotten into a time machine back to 800 years ago that night, looking up. I felt what they felt.

The spirit of sharing your knowledge, the hospitality of welcoming a ship into the shore—all of that sounds very much in line with what I know about the spirit of aloha. Do you think that word, and the practice of Polynesian sailing, are connected?

It’s a word that means different things to different people. Through the lens of pre-Hōkūleʻa ’60s tourism, it meant one thing. Now, with the cultural renaissance, it’s really touched a deeper meaning. It’s really a system of reciprocity—between people and people, between people and the land, between people spiritually.

Alo is your face, and ha is your breath. As a physical representation, aloha was when people used to greet one another—this is pre-COVID—they would touch noses and inhale, and that was an exchange of the most valuable thing you had: your life force, your breath.

How it manifests itself is this giving freely of your knowledge and your resources. And that was one thing that we got to experience as we went around the world and shared our story and were hosted and greeted. And as people are regaining and relearning the cultures and things that made these islands unique and special, the more they’re wanting to share.

I feel like I’m living a daily routine now that’s similar to what my ancestors did, and that feels good—and the first thing I want to do with that feeling is share it with someone. I want to get students onto a canoe and feel how fast they can go. To see what their home looks like from the ocean.

HOPENA POKIPALA

A skilled sailor and a serious big-wave surfer, Hopena Pokipala didn’t just host the Polo team for our photo shoot. He also lent out his very own Hawaiian sailing canoe, which he built himself by hand while in college. Hopena, now 26, uses it to sail around the coast, teaching and carrying on the ancient Polynesian practice, but puts his own spin on it by using his boat—sail and all—to surf waves.

Where are you from, and how’d you first get introduced to sailing?

I’m from Kailua, on Oahu, on the east side—the windward side. In high school, we had a sailing team, and I joined when I was a freshman. I got involved there, did some races, and just fell in love with it. My sophomore year, we had a Hawaiian navigation course. Nainoa Thompson, who spearheaded the Polynesian Voyaging Society and is a huge part of sailing in the modern era, was a guest speaker and invited us to come onto the Hōkūleʻa. That really lit the flame of my passion to learn more about sailing and to get in touch with my culture. I grew up paddling canoes competitively, which is a big sport here, and that seemed like the next step, from paddling to sailing.

Was it difficult to learn that transition from the sailboats you were doing when you first joined the team to the more traditional Hawaiian sailboats?

It was difficult in the sense that there’s no textbook on traditional canoe sailing, when there’s so much literature on regular sailing in the modern day. I had to go ask people how to even rig a canoe to sail. And everyone has their own twist and spin on it. So in that sense it was difficult, but I think it made me learn a lot more. There aren’t too many canoes sailing, and the community is pretty small in general. But once you get the hang of it, it’s very simple.

I’m fortunate to live in my family home. My grandma grew up here, starting in the ’40s, and I have the ocean as my backyard. So, every morning, I try to get in the water. Usually that’s sailing, when there’s good wind. If there’s no wind, I’ll go paddling, surfing, diving, anything. The ocean is a fixture in my life, in that way.

That sounds incredible. And you’ve got your own boats—tell me about those. Do you have a favorite?

The one that we used on the Polo shoot. I built it myself in college. My original goal with it was to do sailing cultural tours out of college—I wanted to be an entrepreneur, so I built this canoe. But it’s difficult to get permits to do that legally, especially in Hawaii, so I’m still working on that. But I do have that canoe. If there’s no wind, I’ll take the sail off and go paddling on it, or catch waves with it. And when there is wind, you put the sail on. So it’s a very multifaceted vessel.

Catch waves on it? Like, surfing with a canoe?

It’s a very unique niche of surfing, but it’s out there. I actually have a picture on my desk here, of this guy named Aka Hemmings. He’s on an outrigger canoe riding, like, a 20-foot wave. I wake up every morning and look at that as inspiration.

That’s a form of traditional canoe surfing without a sail. I do it with the sail—not on huge waves, but it’s really fun. It’s like kiteboarding to surfing—it’s that next step. You can’t do that with the big canoes; they’re bulky and expensive and hard to maneuver. But my canoe is light and easy to move around and get in and out of tricky situations.

How big is the canoe, exactly? That sounds incredible, to navigate that onto a wave.

It’s about 24 feet long, and there are two outriggers. I can fit about four to six people comfortably. I’ve packed it with 12 people before … but that was a bit too much.

It’s named Hōkū Alakaʻi, which means “guiding star.” I built it at a time in my life where this was what I wanted to do, the path I wanted to be taking, and this boat was leading me there. And my grandmother’s nickname is Star, so there was a double meaning there to pay homage to my grandma while also looking forward to my own life and career.

Tell me about the cultural impact tied in with canoe sailing, too. You and Austin are both young, and not only carrying on this tradition yourselves but also teaching it to a new generation.

I definitely feel strongly that we have a responsibility, not just to our family but to our entire culture. In the ’70s with the Hawaiian Renaissance, you know a lot of this stuff was almost completely extinct. We were fortunate enough to inherit and reclaim what our uncles and aunties had done a generation or two before us.

So I definitely feel a sense of responsibility—kuleana in Hawaiian. And it’s cool to see the fruits of their labor pay off. Like right now, my little cousins are in Hawaiian immersion schools. They’re in kindergarten and fluent in Hawaiian. Whereas up until the ’90s, it was technically illegal to speak Hawaiian in schools. So, there’s definitely traction. And everything is building upon everything else.

That word—kuleana—that sounds similar to how Austin described aloha. What meaning do you think that has, aside from its literal one?

Kuleana literally means responsibility, but it’s more than responsibility. It’s almost like a blessing that you’re able to take on. This responsibility that Austin and I are both fortunate to have is the canoe and it being a part of our lives, and we’re fortunate to be able to share this passion.

In the community, it’s something you learn really early on. You admire the people giving back the most, who are going out of their way to teach and to facilitate learning in the community. I grew up admiring that and thinking, “I want to be that kind of a person when I get older.” So kuleana is not just a responsibility—it’s a blessing.

You’re also a very skilled big-wave surfer, right? Did that come before the sailing?

I surf more than I do anything else. That’s my main passion in life: surfing. I grew up boogie boarding on the windward side of the island, and you can’t take surfboards on the bus anywhere here. And we had to commute via bus everywhere to get to our surf spots. So, you go boogie boarding with your friends, catching the bus, until high school, once you start driving. That’s when I got into surfing. So, about the same time as when I got into sailing. In college, I started pushing my limits to the bigger waves, and I got hooked on it.

I’ve heard you’ve ridden some very serious waves.

Growing up, I would see posters of the Eddie Aikau big-wave surf competition, and that was always a goal of mine—I wanted to be out on those big waves, too.

After high school, I got the opportunity to get out there to Waimea and step up my game with some of my friends. The night prior, I couldn’t sleep, thinking about those swells and the huge, 20-plus-feet Hawaiian-style waves. As we were driving up the coast, the closer you got to the North Shore, the louder the waves got until you could hear the waves breaking on the grounds, and the road was shaking, literally. Then we get there, the sun’s about to rise, and there’s a thousand people around the bay, and everyone’s hyping it up.

When dawn cracked, you could start to see the mountains of water—the biggest surf I’d ever seen at that point in my life. My friend Noah took me out there for the first time, and I thought, “This is the moment I’ve been waiting for my whole life.” You see the line of the horizon vanishing beneath the sea level, and everyone’s yelling,, “Go, go, go!” And I remember having tunnel vision, hearing my heart pounding, and then as soon as I committed to standing up, everything went silent. Then the drop happened, and it was just this huge, huge rush of adrenaline and endorphins.

It was addicting. I remember the wind flowing through my face and looking up, at the bottom of this wave that was the biggest I’ve ever surfed in my life, and it was a really powerful moment. Then the wave broke on top of me and I got ragdoll-ed, but I popped up and thought, “OK, that was my first experience at Waimea.” Ever since then, I’ve been hooked.

Can you tell me a little bit about the shoot and what it was like, what you guys did on the boat?

I had one of the coolest moments of my life on the shoot. We just did regular laps around the coast, initially. But then the water safety on set gave us the go-ahead to try to catch a wave with the canoe. So he put the canoe on the back of his jet ski and towed us out onto the surf, the whole canoe with the sail and everything. And we were able to turn around and catch a few waves—it was a really remarkable moment. I didn’t even know you could tow a canoe like that.

Where do you want to take your sailing and surfing and life on the beach? Are there any big goals on the to-do list?

One really big, long-term goal of mine would be to have my community all pitch in and build a voyaging canoe similar to the Hōkūleʻa, tied into the community of Kailua, and get the elementary schools involved. This is happening around all the islands right now. In the next town over, there are a few canoes tied into the elementary school, and the curriculum involves navigation and cultural lessons. I think it’d be cool to have that in Kailua, and maybe eventually every district can have their own sailing canoe.

Right now, it’s a small ember that could ignite a huge fire. I’ve taken some of my cousins out on my canoe. They’re 6 years old, steering and sailing, versus 15 and in the back of the canoe like I was. So that’s already a huge leap, you know? And hopefully that can continue to grow.

- Photograph by Bailey Rebecca Roberts

- Photograph by Bailey Rebecca Roberts

- Photograph by Jay Kerns

- Photograph by Hopena Pokipala

- © Ralph Lauren