High Water Mark

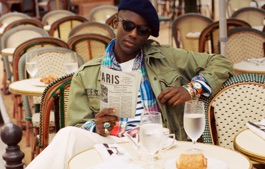

Ralph Lauren is proud to be honored by Riverkeeper for his decades of support for the organization. Here, David Lauren talks to vice chair Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. about the past, present, and future of the group dedicated to keeping New York’s waterways clean

Below, a Q&A below between David Lauren and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. about Riverkeeper’s history, the importance of service, and how environmental rights are tied to civil rights.

When did you first become active with Riverkeeper?I was working as a district attorney in 1984, and I began doing cases for this group of fishermen in upstate New York called the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, which later became Riverkeeper. This was a blue-collar coalition that first mobilized on the Hudson in 1966 to reclaim the river from its polluters. For them, the environment was their backyard. It was the bathing beaches and the swimming holes and the fishing holes of the Hudson River. In 1973, they collected the highest penalty in United States' history against a corporate polluter. They got $200,000 from Anaconda Wire and Cable. They used that money to construct a boat, and they hired me and a permanent Riverkeeper, John Cronin, in 1983 and 1984. Eight years later I became the prosecuting attorney for the group.

Since then we’ve brought more than 300 successful legal actions against Hudson River polluters. The miraculous resurrection of the Hudson has inspired the growth of Riverkeepers now on waterways across North America.

This group is considered a grassroots organization. What does that mean?

The environmental movement really began as a grassroots movement. Twenty million people came out on Earth Day 1970, to demand that the government return to the American people their ancient environmental rights. I remember what it was like before Earth Day. I remember the Cuyahoga River burning for a week and nobody being able to put it out. I remember what the air smelled like in Washington, D.C. We had to dust in our house every day because of soot. And this accumulation of insults drove 20 million Americans out on the street.

Republicans and Democrats and the political system responded. Nixon created the EPA. We passed 28 major environmental laws over the next 10 years and it was all because of the grassroots, because the people really rose up and said, "We're not going to take it any more."

The best thing that people can do is to join an environmental group. That’s the most important thing that anybody can do. It's more important than recycling your garbage or buying a fuel-efficient car. If we have a law on Capitol Hill that says you can’t build a car in this country and you can't import one unless it gets 40 miles per gallon, that battle is really a battle between the environmental community that's representing the public and industry, which is representing its interest in short-term profits. The most important thing people can do is to join an environmental group and give us the support that we need to battle the big shots on Capitol Hill.

Your father was involved with civil rights and a number of different causes. Do you read about what he's done and feel that’s something that you want to take on, or be more personally active in as well?

I was 14 when my father died, so I have a very clear memory of those civil rights battles, and he involved us in all of the issues. But the environmental issue touches on all of that. It’s intertwined. It’s the most important civil rights issue.

You know, we’re not protecting the environment for the sake of the fish and the birds. We’re protecting the environment because we know nature enriches us. And if you look at every environmental issue, you’ll see that the disproportionate burden of environmental injury always lands on the backs of the poor.

If you live in a wealthy neighborhood and somebody says, "We're going to put a landfill or incinerator in your backyard," you're going to make it really expensive for them to put it there. So what they’re going to do is move it around until it lands in a neighborhood where the people do not have the wherewithal to fight it. That is why four out of every five toxic waste dumps in this country are in a black neighborhood. Every environmental issue is a civil rights issue. The largest asset that most Americans have is fresh air and clean water, and beautiful places to take their children. And the poor are the first injured when you start destroying those things.

Was there any wisdom given to you that you share with your family?

I was given a lot of things. A good education, wonderful friends, wealth and access. But none of those things belong to me. They belong to God; they’re on loan to me. I’ve got to use them to do good things for other people, to leave the world a better place.

- BFA

- Photograph by Rob Friedman; courtesy of Riverkeeper

- Photograph by Neil Rasmus; courtesy of BFA

- Photograph courtesy of Riverkeeper

- Photograph by Ann Billingsley; courtesy of Riverkeeper