His Way

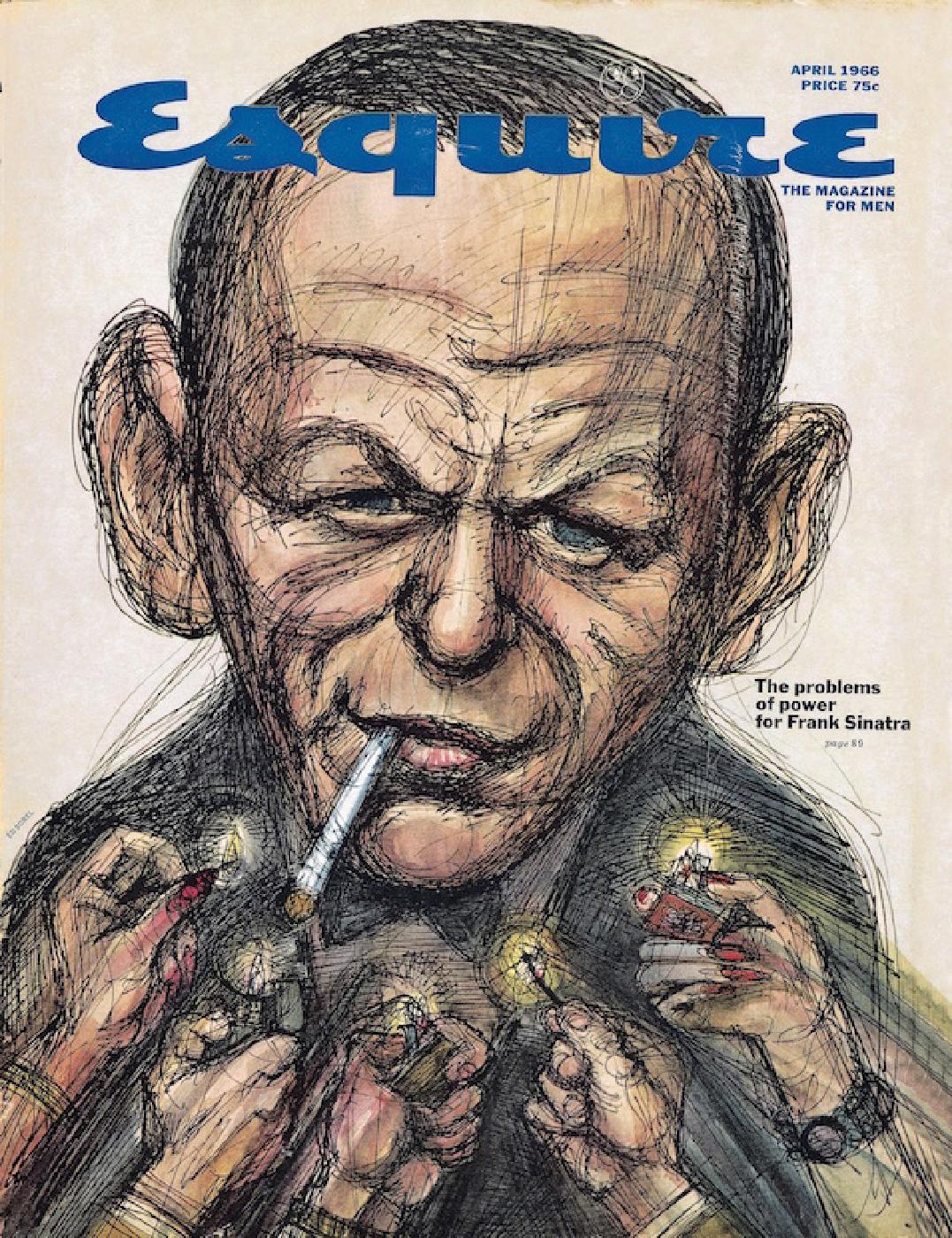

Gay Talese—the journalistic and sartorial legend whose 1966 Esquire profile, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” changed magazine writing forever—talks to Tyler Thoreson about Old Blue Eyes and his significance as a man of styleIn the winter of 1965, Frank Sinatra was on the cusp of 50, and the world was passing him by. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones had ushered in a new sound, a new attitude, and a new look, while Sinatra was facing inconvenient rumors of mafia connections and—worse—looming irrelevance. But where many saw in Sinatra a relic, the legendary Esquire editor Harold Hayes saw a story. And so as Sinatra was preparing for an NBC comeback special, Hayes dispatched a former reporter for The New York Times by the name of Gay Talese to Beverly Hills to capture the scene surrounding the Chairman of the Board.

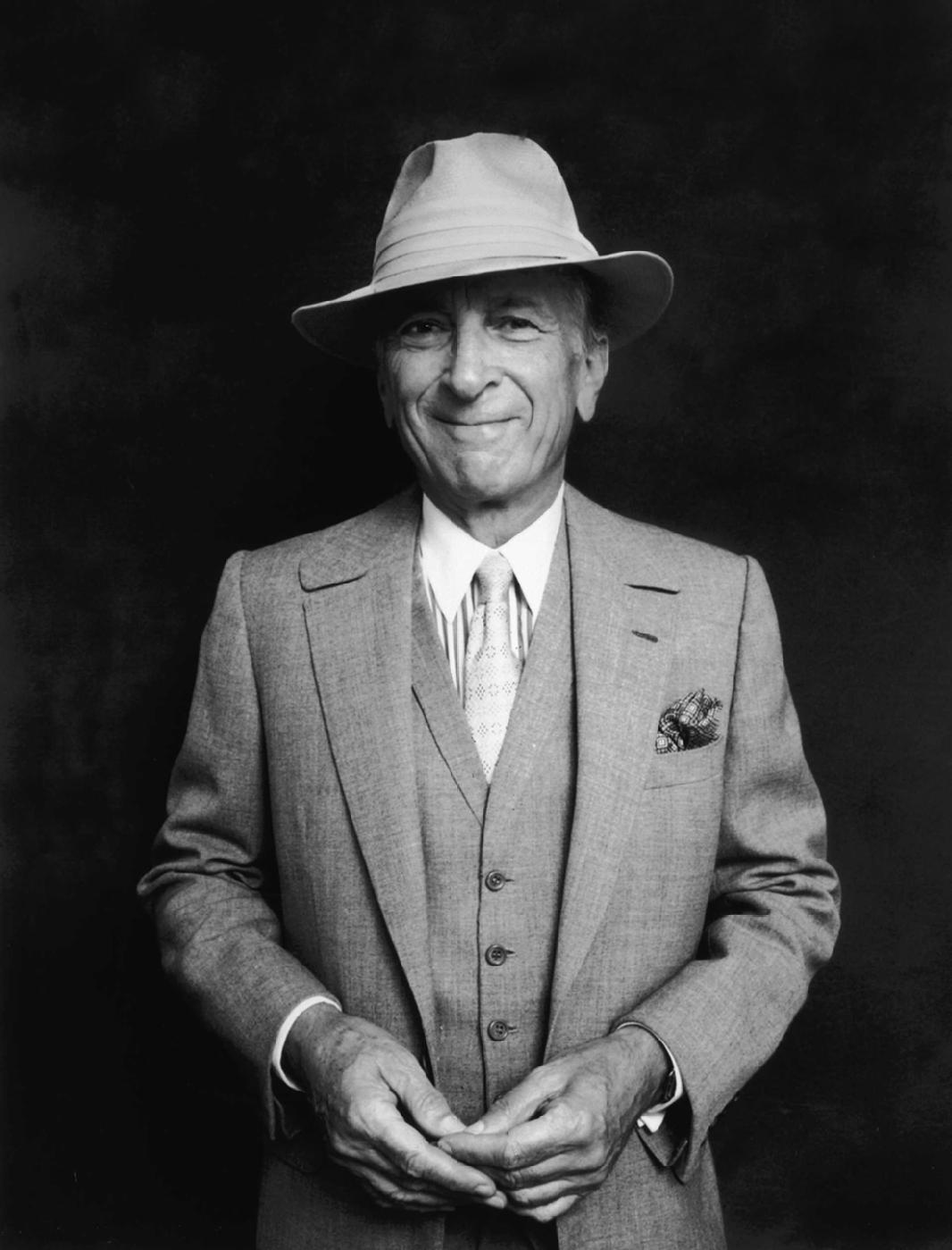

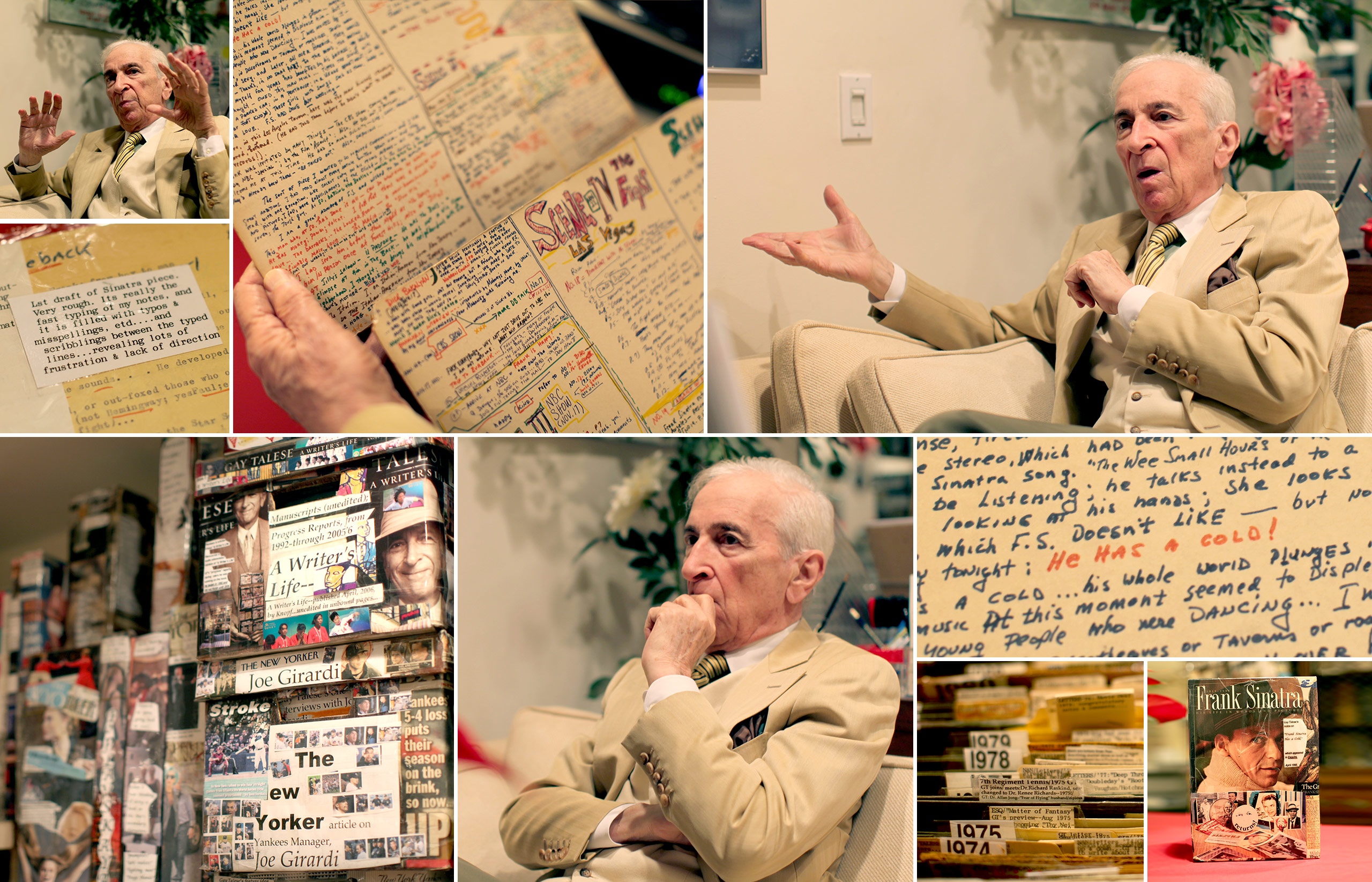

It took some convincing. “I didn’t want to do it,” Talese recalls from a sofa in his “bunker,” the basement office-cum-lair underneath the Upper East Side townhouse that he and his wife, legendary book editor and publisher Nan Talese, have called home for several decades. “Sinatra had been so overdone. When you’re dealing with super celebrities who’ve been in the public eye for a long period of time, and so mesmerized by the magic of their success, and so accustomed to being in this special world … they don’t know who they are,” Talese adds. “If you ask them questions, what’s the point? They’re not people—they are images. They are so accustomed being interviewed that whatever they tell you, they probably have said the same thing and have rehearsed it and are so predictably responsive that you get nothing. I didn’t want to do that.”

He was always on a stage—even on the streets of Las Vegas at four o’clock in the morning

What I wanted to talk about was Sinatra’s style. After all, 50 years later, John, Paul, George, and Ringo’s mop tops and Nehru collars look a bit silly. But Sinatra, with his fedora and meticulously tailored suits, still has plenty to say about how a man should dress.

There’s this great scene in the piece, where Frank has a little back and forth with the writer Harlan Ellison, who’s dressed casually and full of youthful attitude. To Ellison, 49-year-old Sinatra is a dinosaur, yesterday’s news, especially in light of the generational shift going on at that particular moment, in 1965.

The year of the Beatles.

Yes. And here’s Sinatra, fastidious to an extreme. Did the generational shift taking place bring out his inner curmudgeon?

Well, he was accustomed not only to having his own way, but he had his style and he wanted his style to permeate the culture. And then you had a new generation moving up, one that didn’t respect the traditions that Sinatra expected people to buy into. [Yet] he had already worried about obscurity before he got that lucky comeback, and also what he was doing as a way of deference to the new generation—he was dating a woman of that time, Mia Farrow.

Look at Tony Bennett who links up with Lady Gaga. I mean, this is not particularly a unique way of surviving—show business people linking up with whoever is hot, and Sinatra had a history of being with people who are hot.

Yet he didn’t change his look to fit the times.

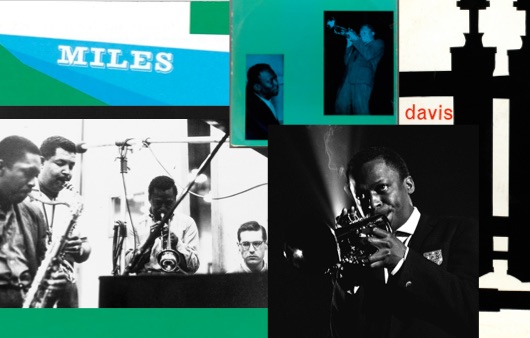

No, he didn’t. When I was there, it was almost like he looked like he was on the cover of an album. The guy with the cigarette and the hat tilted just so.

He was a hat man.

Sinatra didn’t always wear a hat, but he often did. He cared about clothes, and he bought clothes for people. How many celebrity men do you know who buy clothes for other men? Sinatra did that.

At Christmastime he would buy sweaters and jackets for different people in his band. I remember there was a man who was a piano player, who lost his house in a mudslide, and Sinatra bought a whole new wardrobe for this guy—and he knew his shirt size.

There is this great scene in the piece: during the wee hours of the morning in Las Vegas, Frank is carrying around a shot glass of bourbon, and everyone else is loosened up, but Frank is just polished as can be. Was he really that well put together at that hour, or was it really just his attitude that he convinced you he was?

I think he felt like he was always on a movie set; he was always on a stage—even on the streets of Las Vegas at four o’clock in the morning. He also had this extra sense of self that was not in any normal way normal. It was always extraordinary or abnormal that life was a movie, life was a set, life was a stage.

But for him it was. Did he like being on stage? Did he like playing the role of “Frank Sinatra”?

I think so, but if you asked him a question he didn’t like, he’d probably throw a glass in your face.

Did you ever see him less than put together?

No, I never saw him with his jacket off. I never saw him when he wasn’t wearing a tie, come to think of it. But of course, I only saw him when he was “on.”

He had a consistent mode of dress, and so do you.

We’re locked in midcentury fashion.

I pay attention to people who dress in a very traditional and elegant way, people who will spend money on clothes.

As a journalist, you talk about dressing for the story as a sign of respect. Yet these days, things are much more casual. Do you feel like dressing up is your act of rebellion against that?

Tyler, from the vantage point of a young person such as you [Ed. note: Talese is charitably stretching the definition of “young.”], it might be true, but what it is with me is really a respect for the role of a reporter—which I think reporters lack. … Sinatra was carrying through on standards of the 1950s when all men wore hats.

No matter what they did for a living. What can men from today learn from Sinatra and his approach to style?

Well, I think that Sinatra had a real image about manhood. Sinatra was interested in masculinity and modishness. Not only the women were glamorous—the men, also. In that period, men in high office—political life, business life, advertising—they all dressed pretty well. The 1960s changed all that.

People I meet in the NYU journalism department, where I might have given a little talk—even if I were on the faculty, I wouldn’t dress like the faculty people because they want to be young again. They want to become compatible with their students. I don’t want to be compatible with the students—I’m not.

You want them to rise to your level?

I want them to know that there is a hell of a difference between me and them, and that’s the way it is. And if they are great reporters and good writers, then that’s a different story.

Gene Kelly singing and dancing in the rain—that’s effortless. It took him months to get every step in the rain, boy, to make that seem effortless. Joe DiMaggio made it look easy, but it wasn’t easy to catch those fly balls. Nothing that looks easy is easy. Nothing.

- The LIFE Picture Collection

- PHOTOGRAPH BY GJON MILI

- PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF GAY TALESE

- PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ESQUIRE MAGAZINE

- PHOTOGRAPHS BY GORDON HARRISON HULL