Style

The RL Q&A: Jimmy Nelson

The celebrated photographer talks to Nicole Phelps about his groundbreaking book, Before They Pass Away; shooting the Fall 2015 Ralph Lauren Collection campaign; and why a camera is ultimately a catalyst for conversation

British photographer Jimmy Nelson has dedicated much of his career to traveling to the remotest regions of the world and documenting vanishing indigenous peoples in their traditional dress. His stunning and eye-opening 2013 book, Before They Pass Away, collects three years of his work and features such diverse tribes as the Kalam of Papua New Guinea, the Chukchi of Siberia and the Mursi of Ethiopia. The work has garnered him unprecedented attention, not least of all from the BBC, which has partnered with him on an upcoming documentary series. In addition to his globe-trotting anthropological work, Nelson takes the occasional fashion assignment, including the Fall 2015 Ralph Lauren Collection campaign, which was shot in the north of Finland. We tracked him down while he was on vacation in Ibiza, where he shares a home with his wife and their three teenage children.

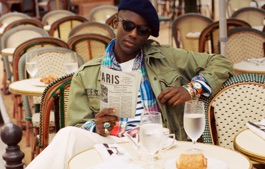

Jimmy Nelson in Goroka, Papua New Guinea, where he photographed indigenous peoples for his 2013, book Before They Pass Away.

You’ve said that your first trip to Tibet happened “by accident.” What was that experience like?

It was in 1985 and 1986, and Tibet had been closed for about 30 years. I just went to get lost. I wanted to go to a place that I felt comfortable in. I’d spent quite a bit of time in China as a kid, so I had an idea of what [to expect]. There was this whole issue with my visual change of appearance [due to alopecia], and I wanted to fit in with other bald kids. I don’t want to make it sound like any grand journey; I didn’t set off to cross Tibet. I started at one end, and the only way of getting out was the long way around, so I went across the length.

That must’ve been quite an adventure for a young man. You were 17 or 18. Is it fair to say that you found your passion for photography there?

I started the journey. I used a camera to document the people that I met. I was not a photographer prior, but I was a creative child. Thirty years later, I would argue that I [still] don’t see myself as a photographer. I’m not obsessed with lenses, with shutter speeds, with camera straps. It’s purely a means to an end of making interactions. I think a lot of photographers hide behind their camera. For me, it’s a catalyst for conversation.

It was in 1985 and 1986, and Tibet had been closed for about 30 years. I just went to get lost. I wanted to go to a place that I felt comfortable in. I’d spent quite a bit of time in China as a kid, so I had an idea of what [to expect]. There was this whole issue with my visual change of appearance [due to alopecia], and I wanted to fit in with other bald kids. I don’t want to make it sound like any grand journey; I didn’t set off to cross Tibet. I started at one end, and the only way of getting out was the long way around, so I went across the length.

That must’ve been quite an adventure for a young man. You were 17 or 18. Is it fair to say that you found your passion for photography there?

I started the journey. I used a camera to document the people that I met. I was not a photographer prior, but I was a creative child. Thirty years later, I would argue that I [still] don’t see myself as a photographer. I’m not obsessed with lenses, with shutter speeds, with camera straps. It’s purely a means to an end of making interactions. I think a lot of photographers hide behind their camera. For me, it’s a catalyst for conversation.

I think a lot of photographers hide behind their camera. For me, it’s a catalyst for conversation.

Your camera is a means to an end, yet you take such exquisite photographs. How did you learn to use it?

Today, everybody takes pictures. Photography is the first-ever global language. My kids’ pets have cameras attached to their heads—GoPros. If the pictures you’re making are not exquisite, if they’re not made with your heart and soul, people are not going to look at them. I use analog cameras—these 4-by-5- and 8-by-10-sheet-film cameras. When you use something very old-fashioned, very difficult and cumbersome, and quite expensive, you become even more focused on the subject matter. It’s easy to put your finger on the button and fill up eight cards with 10,000 pictures. If you’ve only got 10 sheets of film, you make sure those 10 sheets are absolutely exquisite. Rather than make 1,000 pictures a day, you make one picture in two days. It brings you into this state of visual Zen of looking at the landscape, the people, the light, the composition. You know that one exposure has to work.

You don’t share a language with many of the people you photograph. How do you build those relationships? How do you make sure that single exposure works?

We all want to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be put on a pedestal. To persuade the sitter, you essentially have to worship them: You have to physically get on your bended knee, you have to sweat, you have to cry, you have to prostrate yourself to the subject. If you prostrate yourself to your subject, they will end up shining.

Your book, Before They Pass Away, has gotten a great deal of attention. I wonder if people are moved by your photographs because the situation of indigenous tribes looks intractable. Where do their customs fit into the future?

I’m not going to say, “Guys, you’ve got to spend the rest of your lives standing in a skirt with a spear in your hand waiting for the sun to rise.” That would be very patronizing. What I am saying is, “You have something extraordinary. You have a different kind of wealth, a wealth that is as valid as what’s in our bank accounts.” It’s a wealth of contact with ourselves, contact with tradition, with our physicality, with nature. It’s very valuable. We have to encourage them to keep it in some way or another.

Not easy, I imagine.

It’s extremely complicated. And a lot of what I say is controversial. But if we don’t interact with and discuss this subject, it won’t sort itself out, and due to civilization and globalization, [these tribes] will be gone in 10 years time, I promise you.

Does a project like Before They Pass Away ever end?

There’s this idea of “retribing” [that I’m interested in]. There are many young, contemporary groups of people around the world defining a tribal and cultural way of living, and I’d like to document that.

Today, everybody takes pictures. Photography is the first-ever global language. My kids’ pets have cameras attached to their heads—GoPros. If the pictures you’re making are not exquisite, if they’re not made with your heart and soul, people are not going to look at them. I use analog cameras—these 4-by-5- and 8-by-10-sheet-film cameras. When you use something very old-fashioned, very difficult and cumbersome, and quite expensive, you become even more focused on the subject matter. It’s easy to put your finger on the button and fill up eight cards with 10,000 pictures. If you’ve only got 10 sheets of film, you make sure those 10 sheets are absolutely exquisite. Rather than make 1,000 pictures a day, you make one picture in two days. It brings you into this state of visual Zen of looking at the landscape, the people, the light, the composition. You know that one exposure has to work.

You don’t share a language with many of the people you photograph. How do you build those relationships? How do you make sure that single exposure works?

We all want to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be put on a pedestal. To persuade the sitter, you essentially have to worship them: You have to physically get on your bended knee, you have to sweat, you have to cry, you have to prostrate yourself to the subject. If you prostrate yourself to your subject, they will end up shining.

Your book, Before They Pass Away, has gotten a great deal of attention. I wonder if people are moved by your photographs because the situation of indigenous tribes looks intractable. Where do their customs fit into the future?

I’m not going to say, “Guys, you’ve got to spend the rest of your lives standing in a skirt with a spear in your hand waiting for the sun to rise.” That would be very patronizing. What I am saying is, “You have something extraordinary. You have a different kind of wealth, a wealth that is as valid as what’s in our bank accounts.” It’s a wealth of contact with ourselves, contact with tradition, with our physicality, with nature. It’s very valuable. We have to encourage them to keep it in some way or another.

Not easy, I imagine.

It’s extremely complicated. And a lot of what I say is controversial. But if we don’t interact with and discuss this subject, it won’t sort itself out, and due to civilization and globalization, [these tribes] will be gone in 10 years time, I promise you.

Does a project like Before They Pass Away ever end?

There’s this idea of “retribing” [that I’m interested in]. There are many young, contemporary groups of people around the world defining a tribal and cultural way of living, and I’d like to document that.

Natives of the Chele Village, located in the Upper Mustang region of Nepal, as seen in Before They Pass Away. For more photos from the book, click through our slideshow.

Tribesmen from Rah Lava, a remote island belonging to the Banks Islands group of the South Pacific nation Vanuatu.

The Samburu people of Kenya are cattle-herding Nilotes who relocate every five to six weeks to keep their livestock fed.

Body ornaments are a tradition for tribes indigenous to Goroka.

The nomadic Nenets, a group of reindeer herders, live in the extreme climate of Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula. Temperatures drop to minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit in winter and rise to 95 degrees Fahrenheit during summer months.

“A gaucho without a horse is only half a man,” Nelson’s website states of these nomadic Patagonian people, who spend their days herding and catching cattle.

Native to Tanzania’s Serengeti region, a Maasai warrior is responsible for protecting his family’s livestock from human and animal predators.

Perak women from the Thiksey Monastery in Ladakh, a cold desert in northern India.

Temple dancers at the Thiksey Monastery, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery founded in the 15th century.

Descendants of Turkic, Mongolic and Indo-Iranian indigenous groups, the Kazakhs are seminomadic people who continue to practice the ancient art of training eagles to hunt for rabbits, foxes and wolves.

From a very early stage, you balanced your personal work with more commercial work. How do they impact each other?

I started out doing personal work in my late teens. In my 20s, I did a lot of coverage of wars and poverty, but again, I wasn’t a journalist. I was curious about how these people lived, the emotions we could share with one another. Then I met my wife. I wanted a family, but that was an impossible way to have a family, so I evolved into doing commercial photography. It was fairly successful for a while, but it was always for the sake of getting the bills paid and making sure I was asked again. Five or six years ago, I essentially stopped my commercial work. The images that I made in Before They Pass Away were purely for me at first; it’s what I see and what I feel, what I think is beautiful. When Ralph Lauren came and asked me to shoot the campaign, that completed the circle. The Ralph job is a style and aesthetic that I love, and it’s very similar to what I do in my own projects. So, it’s a fantastic meeting.

You found yourself with a sizable crew in Finland.

I ended up taking one professional assistant and two members of my family. [I brought] my wife, Ashkaine Hora Adema, who I used to work with when I worked as a commercial photographer. She sees things in a different way, and together we see everything, ha-ha. My eldest daughter also works with me a lot, so she can learn what it is to work hard in this world. It wasn’t necessarily just a commercial job; it was a reconnecting with family members working together. I took a four-year break from commercial work to focus on Before They Pass Away, and it was really like coming home to work with such an amazing crew again, especially because everybody was so professional and experienced.

I started out doing personal work in my late teens. In my 20s, I did a lot of coverage of wars and poverty, but again, I wasn’t a journalist. I was curious about how these people lived, the emotions we could share with one another. Then I met my wife. I wanted a family, but that was an impossible way to have a family, so I evolved into doing commercial photography. It was fairly successful for a while, but it was always for the sake of getting the bills paid and making sure I was asked again. Five or six years ago, I essentially stopped my commercial work. The images that I made in Before They Pass Away were purely for me at first; it’s what I see and what I feel, what I think is beautiful. When Ralph Lauren came and asked me to shoot the campaign, that completed the circle. The Ralph job is a style and aesthetic that I love, and it’s very similar to what I do in my own projects. So, it’s a fantastic meeting.

You found yourself with a sizable crew in Finland.

I ended up taking one professional assistant and two members of my family. [I brought] my wife, Ashkaine Hora Adema, who I used to work with when I worked as a commercial photographer. She sees things in a different way, and together we see everything, ha-ha. My eldest daughter also works with me a lot, so she can learn what it is to work hard in this world. It wasn’t necessarily just a commercial job; it was a reconnecting with family members working together. I took a four-year break from commercial work to focus on Before They Pass Away, and it was really like coming home to work with such an amazing crew again, especially because everybody was so professional and experienced.

The Fall 2015 Ralph Lauren Collection campaign, photographed by Nelson.

Have you turned your children on to photography?

My wife and I have turned them all on to being creatives. But none of them would ever see themselves as photographers, and I think that’s also a generational thing. There aren’t any photographers anymore in my eyes. There are visual creators, with film, with photography, with writing and curating. All three of them will end up going into a creative branch, but it won’t be just photography.

My wife and I have turned them all on to being creatives. But none of them would ever see themselves as photographers, and I think that’s also a generational thing. There aren’t any photographers anymore in my eyes. There are visual creators, with film, with photography, with writing and curating. All three of them will end up going into a creative branch, but it won’t be just photography.

You’ve been to 44 countries. Where to next?

I’m planning to go to three specific areas in the near future. One is back to the Amazon. The Amazon is very difficult to get into because it’s highly protected. It’s very political. I tried before without a lot of success, but now I’ve been invited by various groups, so they’re taking me in. I want to spend a lot more time in Siberia, another part of the world that has not been excessively documented because of its inaccessibility and its scale. And also back down to the Pacific Islands.

You’ll have to be careful with your fingers in Siberia. Didn’t they get stuck to the metal plate in your camera when you were shooting there for your book?

Things are always happening. That story is important: Being vulnerable really is the only way to show who you are. By being very emotional and very fallible, you make fantastic connections.

Did anything particularly emotional happen in Finland at the shoot?

It did. Ralph Lauren has used a stable of photographers over the last few years, and I was an experiment. They were all a bit nervous about it. I can understand that—investing so much time and money to send a huge crew to Finland. But by the end we had a dinner, and there were tears—positive tears—saying it was a very human way of working together. It felt like family.

How do you ensure that atmosphere exists on a photo shoot with so many people running around?

When I work, nothing else counts. I don’t feel any other need. I don’t feel the lack of sleep, I don’t need to eat and I don’t feel the cold. Sometimes that is too demanding, but at the end of a shoot everybody knows we got the best results possible. And that is happiness. That’s what the whole crew remembers, and that is what you see in the pictures: total dedication. I’m very self-confident in what I want and how to achieve it, but we have to achieve it in a balanced, human way, without me shouting four-letter words from the top of the tree.

That’s a good life lesson for non-photographers as well.

There are some extraordinary photographers in the world who can be difficult, yet come out with art at the end of it. I’d rather come out with everybody being friends.

I’m planning to go to three specific areas in the near future. One is back to the Amazon. The Amazon is very difficult to get into because it’s highly protected. It’s very political. I tried before without a lot of success, but now I’ve been invited by various groups, so they’re taking me in. I want to spend a lot more time in Siberia, another part of the world that has not been excessively documented because of its inaccessibility and its scale. And also back down to the Pacific Islands.

You’ll have to be careful with your fingers in Siberia. Didn’t they get stuck to the metal plate in your camera when you were shooting there for your book?

Things are always happening. That story is important: Being vulnerable really is the only way to show who you are. By being very emotional and very fallible, you make fantastic connections.

Did anything particularly emotional happen in Finland at the shoot?

It did. Ralph Lauren has used a stable of photographers over the last few years, and I was an experiment. They were all a bit nervous about it. I can understand that—investing so much time and money to send a huge crew to Finland. But by the end we had a dinner, and there were tears—positive tears—saying it was a very human way of working together. It felt like family.

How do you ensure that atmosphere exists on a photo shoot with so many people running around?

When I work, nothing else counts. I don’t feel any other need. I don’t feel the lack of sleep, I don’t need to eat and I don’t feel the cold. Sometimes that is too demanding, but at the end of a shoot everybody knows we got the best results possible. And that is happiness. That’s what the whole crew remembers, and that is what you see in the pictures: total dedication. I’m very self-confident in what I want and how to achieve it, but we have to achieve it in a balanced, human way, without me shouting four-letter words from the top of the tree.

That’s a good life lesson for non-photographers as well.

There are some extraordinary photographers in the world who can be difficult, yet come out with art at the end of it. I’d rather come out with everybody being friends.

Formerly executive editor of Style.com, NICOLE PHELPS is now director of Vogue Runway.

- PHOTOGRAPH BY JIMMY NELSON; COURTESY OF RALPH LAUREN CORPORATION

- PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF JIMMY NELSON

- SLIDESHOW PHOTOGRAPHS BY JIMMY NELSON

- PHOTOGRAPHS BY JIMMY NELSON; COURTESY OF RALPH LAUREN CORPORATION