Wimbledon has its grass courts, strawberries and cream, and time-honored traditions. The French Open has its clay. But there’s only one tennis major that takes as its lifeblood the electricity and energy of New York City—the US Open in Flushing Meadows, Queens, where the sport’s top players (and a few ball boys and girls ) withstand loud airplanes, screaming fans, and pressure-packed late-night matches to create some of the world’s most exciting tennis. Compared to the quietness of Wimbledon, where spectators rarely whisper during points, the US Open is more like a boxing match: electric and loud. There’s nothing like it in tennis.

“It’s a tough place to be, very demanding, very tiring mentally, all the noises and so on,” says Ivan Lendl, who won the Open three years in a row, from 1985 to 1987.

In the dark, a close match brings even more energy, and fervor, to the crowd and players. “The night sessions—it’s electrifying,” says five-time US Open champion Roger Federer. Andy Roddick, the retired American star who won the Open in 2003, says there’s “a certain energy unlike any other tournament. It’s probably not only a tennis tournament but an event.”

An event, indeed—one that draws a New York coterie of celebrity tennis fans that includes everyone from Jay-Z to Anna Wintour (who provides unwavering moral support to Federer from behind her ever-present black sunglasses).The tournament had a more genteel beginning in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1881, where it remained until the event (then known as the US National Championships) first came to New York in 1915. It briefly moved to Philadelphia but returned to New York for good in 1924, settling at the burgeoning West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens. It was the first year the US National Championships were officially designated a grand slam event by the International Lawn Tennis Federation.

History of all kinds was made on the then-grass courts of the tournament. In 1957, Althea Gibson, who grew up playing paddle tennis on the asphalt streets of Harlem, became the first African-American to win a title in the US Nationals 10 years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in Brooklyn. In 1968, the first year in what’s now known as the Open era of tennis, American Arthur Ashe won the men’s tournament in five wild sets over Tom Okker of the Netherlands. Ashe, still registered as an amateur at the time, couldn’t earn prize money. He had to forgo $14,000 in winnings and instead collected $280 in expenses.

As time passed, the tournament became more popular as tennis became a more accessible sport. Crowds filled the 15,000 seats at the West Side’s main stadium to cheer just as passionately at matches as they did at the now-classic rock concerts (the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan) that took place there.

The intensity soon grew too much for the stadium, for both players and ticket-holders. Perhaps the wildest year in the Open’s history came in 1977, the last held in Forest Hills (and the end of a brief run in which the tournament was played on green clay). The screams and strife among the spectators matched the brash attitude of Jimmy Connors. One fan was shot in the leg by a stray bullet that came from a nearby apartment. And when the men’s final was over, Connors ran off before the trophies were presented (he despised the final call made by a line judge). Fans didn’t care. They were too busy lifting up the winner, Guillermo Vilas.

In 1978, the tournament moved to its new hard-court home in Flushing, Queens. Bustling and diverse, Flushing is nothing like the reserved and wealthy areas surrounding the All-England Tennis Club and Paris’s staid Roland-Garros. Aside from a preponderance of residents and restaurants from nearly every culture in the world, Flushing had a slightly less welcome feature: a proximity to LaGuardia Airport. It’s a testament to New York’s bona fides as a tennis city that in 1990 Mayor David N. Dinkins fought to have flight takeoffs diverted to somewhere other than right over the stadiums.

Not that the noise mattered much to the players who won, like New York’s favorite tennis son, John McEnroe, who reflects the city in every way. He grew up in Douglaston, Queens, and his brash, relentless (and stylish) persona made him into the sort of player Americans had never seen before. He won four Open titles, in 1979, 1980, 1981, and 1984.

But it is Flushing’s uncanny ability to inspire late-career greatness from veteran players that’s most remarkable. Case in point: Connors’s out-of-nowhere comeback in 1991. By then his temperament had softened, the public had warmed to him, and so everyone cheered when, a few days from age 39, he came back against John’s brother Patrick McEnroe to win his first-round match in five sets. And then he kept going, including one of the most memorable matches in the US Open’s history, a five-set, two-tiebreak victory against his former protégé, Aaron Krickstein.

“I’ve played a lot of brutal matches, but none ever like that,” Connors has said. “None ever that I walked off the court and felt like that, ever.” Though his late-career run was cut short, he added, “I always say that’s the best 11 days of my career—and it was.”

Perhaps just as extraordinary as Connors’s comeback was a late-night event in 2005 starring Andre Agassi. Buoyed by an electric crowd, 35-year-old Agassi, long past his prime, came back from a two-set deficit to beat fellow American James Blake in five. The match ended at 1:09 a.m.

Electrifying tennis that extends deep into the night has become a US Open signature. There have been five Open matches that lasted well past 2 a.m., including two since 2012. Kei Nishikori survived one of these, in 2014, and was impressed with the members of the crowd who stayed until the end. “Very happy to see a lot of people even [at] 2 a.m.,” he told the Times after his match. “I don’t even know how they go back home.” (They likely took the 7 train, which runs all night and adds to the local vibe.)

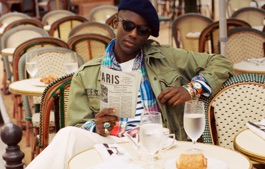

These days, the NYC flavor has spread to the concessions, which are worthy of the host city. The tournament now draws outposts of some of New York’s finest purveyors of burgers, barbecue, oysters, tacos, sushi, curries, and much more. It even has its own official cocktail and New York’s answer to Wimbledon’s Pimm’s Cup—the honeydew-garnished Honey Deuce. Plus, of course, a Polo Ralph Lauren shop where limited-edition US Open gear will be available (including an all-new Create Your Own Polo Shirt experience exclusive to the tournament).

All this and more can be enjoyed in the run-up to the finals, which take place in a beautiful, 23,771-seat stadium that features a new $100 million retractable roof. It’s named for the man who collected $280 for winning the tournament, Arthur Ashe.

And further proof that anything can happen at the Open.- Photograph by Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

- Courtesy of Ralph Lauren Corporation