Peak

Performer

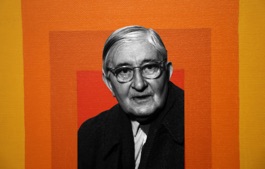

In celebration of the National Park Service’s recent centennial, we talked to renowned mountaineer Conrad Anker about his favorite park, the Meru effect, and the perils of climbing with a 300-pound camera

Conrad Anker has seen his share of the world. A man who’s made his career scaling treacherous terrain, he’s hit blood-thinning heights in the Himalayas and Antarctica, and worked his way through several passports finding new peaks to summit. In 2015, he appeared in the documentary Meru, which chronicled his unprecedented journey up the “Shark’s Fin” mountain pass alongside Jimmy Chin and Renan Ozturk (the film won the documentary Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival).

Where do you go once you’ve reached the top? If you’re Anker, you go back to your roots, which are easiest to find in your own backyard, in America’s national parks. “The park system has been referred to as America’s greatest idea,” Anker says. “And to be able to, in this day and age, find rest, relaxation, and rejuvenation in the mountains, that’s really a key component of being outdoors.” Anker has done his share of climbs in the parks themselves. “Much of the best climbing in the US is in national park sites,” he says. “As climbers, we really appreciate it, and we feel an obligation to be stewards.”

On the eve of the National Park Service’s 2016 centennial, Anker took time out to speak with RL Mag about his favorite parks; the sweeping 3D IMAX film he’s featured in, National Parks Adventure; and the dishwasher-size camera that made it all possible.

You appear in the movie alongside your son, Max, and his friend the artist Rachel Pohl. What’s it like to play yourself on camera?

We do play ourselves, so to speak, and we travel around the West. We’re kind of like mini guides. Rachel is great, she smiles all the time, and Max is inquisitive and a good photographer, so that was reflected in the film. When you’re shooting digital, you just have the camera on, and you’re in the background—you can really catch moments in a very authentic way. If you’ve seen the film Meru, it’s in that style. Here, we have a very specific story we need to follow, and we need to get it done in 40 minutes, so we have to make sure each of our scenes is strong.

Do you have a favorite park?

That’s a tough one, because they’re all so beautiful in one way or another. Certainly Yosemite is close to where my family is, and I love the desert; those areas are really fantastic. But yeah, there are 410 of them, so it’s hard to choose which one is the best. Being here in Montana, Yellowstone is close by, so I really enjoy that. I think in general whichever one you’re closest to.

What was the toughest place to shoot?

Devil’s Tower was probably the most work, because getting the camera on location was really difficult. We were on El Matador, which is a popular climb there. It’s probably about a 200-foot-long crack, and we had to climb up it. Getting to the top was just the first part of it, and then we had to get the IMAX camera set up. It took us three days just to get it in there, and then we’d rehearse, rehearse, do it again, rehearse, rehearse, do it again.

So how big was the camera?

The 3-D camera is about the size of a dishwasher and about 300 pounds, and the 2-D is about the size of a microwave with a thousand whistles attached to it. So either way they’re pretty big, and getting them up on the cliff was difficult, because we couldn’t hoist them up and we couldn’t drag them up, we had to basically take turns body-hauling them up, which was quite a bit of work.

How long would that take unencumbered?

On El Matador? If it was just you and me, and we were totally keen? We could do it in 45 minutes. Not to the summit of Devil’s Tower, but to do that one climb.

Not if it were you and me—I’d slow you down.

We’ll call it 47 minutes.

Speaking of tough climbs, congratulations on Meru. How are you handling its success?

It’s been great. The film has been very favorably received by both the core climbing audience and the sort of open demographic, people who want an engaging human story. Deep gratitude to Jimmy and Renan for filming it on the mountain, and then to Chai [Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi] and Jimmy both, for editing it, putting it together and bringing it to the screen. There’s no way I would have been able to do that. I would have had a couple pictures and a story, but in the end that’d be all I’d have. That was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I’ll never do anything the size of Meru again.

Any parting words on the National Parks movie?

Some people are very aware of the parks, and it’s what they do every summer. And for other people, they kind of know about them, but they’re not really going out there. For the centennial, the National Park Service has extended open access to all parks to fourth graders and their families. That’s kind of the big deal. It’s a great way to get families out there. [And the movie] is certainly an introduction, and something that makes people want to go do it.

- Photograph by Barbara MacGillivray; courtesy of MacGillivray Freeman Films

- Photograph by Dmitri Fomin; courtesy of MacGillivray Freeman Films

- Photographs by Barbara MacGillivray; courtesy of MacGillivray Freeman Films

- Photograph by David Fortney; courtesy of MacGillivray Freeman Films