Souvenirs In Style

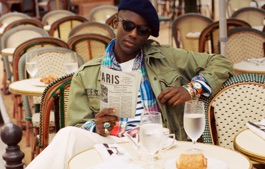

Tracing the history of the tour jacket, from soldier’s souvenir to expression of personal styleUnlike dedicated collectors of fashion, California-based artist Steven Vandervate didn’t have to fork over thousands of dollars for a vintage souvenir tour jacket—his dad handed one down to him. Stationed in Seoul from 1955 to 1956, Vandervate’s father and a few members of his US Air Force unit took their standard-issue MA-1 jackets to an off-base silk-screener. The design applied to the back of the jacket features American and Korean flags at the top, and at the bottom are the years he served, represented by the Korean calendar as 4288–4289. In the center, the Korean peninsula is split by the ultimate symbol of ferocity and power: a dragon.

It was a style pioneered a few years earlier in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, where local craftsmen and members of the U.S. 7th Fleet created the sukajan, or “souvenir jackets,” as they came to be known. The originals combined varsity jacket styling with common Asian motifs rendered in exquisite embroidery and references to soldiers’ specific military units. And because they frequently included the location and the dates of tours of service, the pieces are also often called “tour jackets.”

W. David Marx, an American fashion historian based in Tokyo, charts the long history of give-and-take between these two cultures in his 2015 book, Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style. In it, he also delves extensively into the history of souvenir jackets. That history began shortly after the end of World War II, when a company called Toyo Enterprise started producing rayon versions of letterman jackets and selling them on base exchanges.

“They grew very popular and spread over time to shops outside of military bases, most famously in Yokosuka near the US Navy base,” Marx says. “Soldiers . . . would do R & R in Japan, so it’s likely Japanese makers started producing new versions for them.”Eventually, Japanese locals came to embrace these garments, turning them into both fashion and political statements. Youths found inspiration in American style in the late 1940s, and the ones near Yokosuka began wearing the sukajan in what Japanese fashion illustrator Yasuhiko Kobayashi has called “colonial chic.” By the late ’60s, Marx says the jackets had become a central part of a “young punk” subculture, itself an offshoot of yankii (a transliteration of Yankee).

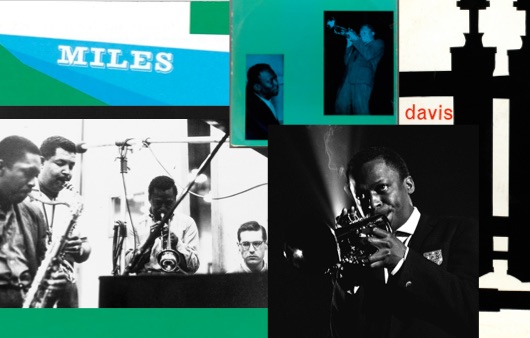

Like many of today’s wardrobe staples that originated with members of the military, tour jackets became popular when they were first worn outside of the armed services and have had periodic fashion moments ever since. This has been helped in large part by the music industry: The Beatles commemorated their 1964 tour of Great Britain with black satin jackets that featured white embroidery on the back. Soon after, Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones was photographed wearing a sukajan, and by 1982 the band was selling satin tour jackets. These days, it’s hard to name a touring musician or group who hasn’t offered something similar, from Mötley Crüe and Michael Jackson in the ’80s to Justin Bieber and Beyoncé today.

- Courtesy of Ralph Lauren Corporation

- Courtesy of Jet Pilot Overseas

- Photograph by Bob Collins; Courtesy of the Estate of Bob Collins/Museum of London