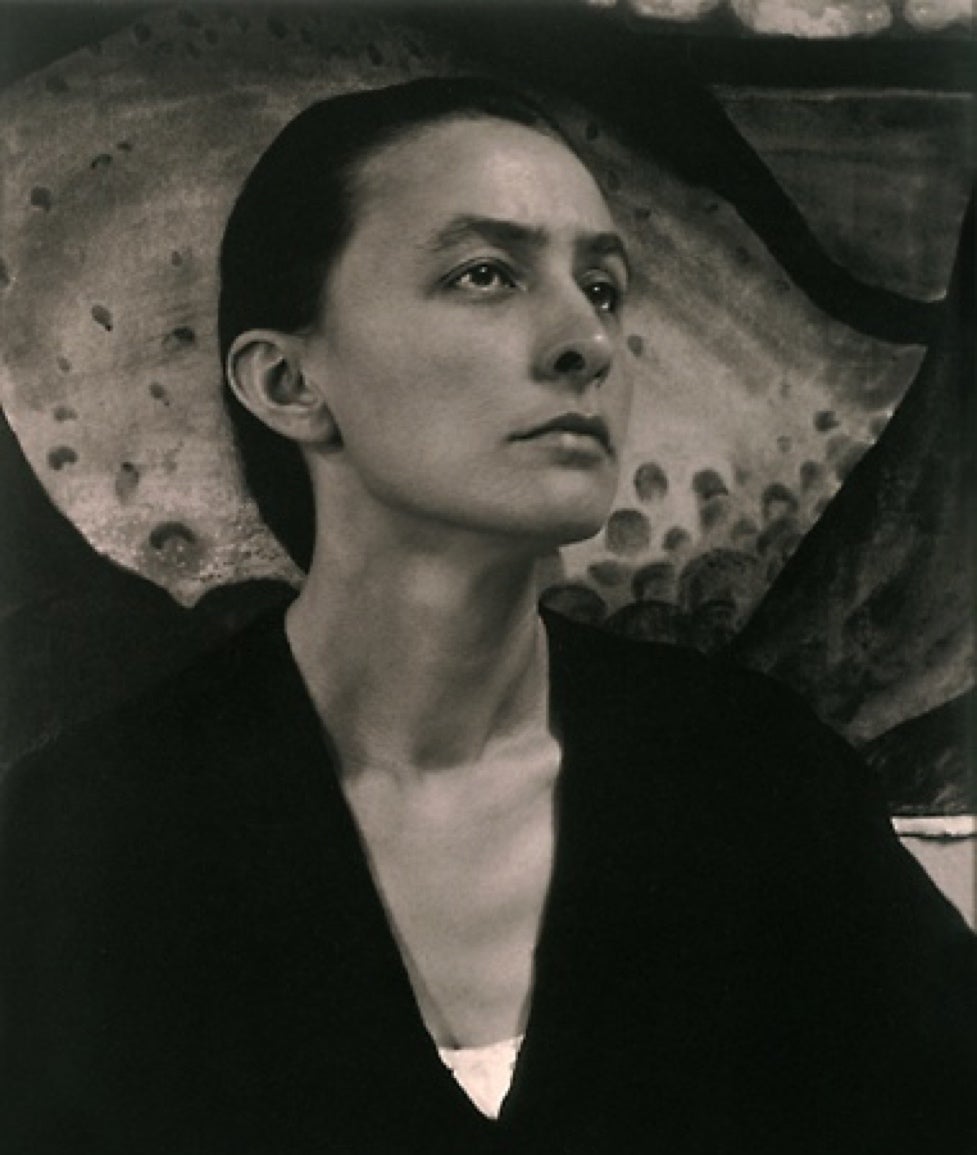

The name Georgia O’Keeffe summons painterly images of unfolding flower petals, floating animal skulls, and wrinkled mountains, but almost as indelible in the American imagination is imagery of the artist herself. A frequent portrait subject, O’Keeffe the woman is seared in modern consciousness: a small and serious figure, hair pulled back, poised and wanting nothing. Integral to the quiet power of this persona is her wardrobe: unadorned, androgynous, simple yet distinctive enough to establish icon status alongside her work.

Georgia O’Keeffe arrived in Manhattan in 1918, a 30-year-old art teacher from Texas with an artistic career in which Alfred Stieglitz—photographer and her eventual husband—saw great promise. “She had an aesthetic before she had a painting,” says Wanda Corn, author of Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern. “Whereas other artists grow into a more mature signature style, it was native to O’Keeffe. She had a less-is-more aesthetic from the very beginning.” Indeed, photographs of the artist as a teenager and young teacher show an extraordinary consistency of fashion: silhouettes unbroken in flow and overwhelmingly black and white—the contrast that would become her hallmark.

Decades before the celebrity that would crown her by the ’70s, O’Keeffe’s sartorial decisions were a matter of practicality and uniform rather than an effort to create a mystique. She opted for soft lines that emphasized outline over interior decoration, monochromatic palettes, and unadorned garments—always tied or buttoned at the wrists. She found her footing professionally while clad in long-sleeve dresses, coats, blouses with pintucked panels, and simple cloche hats. O’Keeffe sewed much of what she wore in the early days: her closet archives evidence of a master seamstress whose skill for stitching a fine line matched her ability for graphic painting. At Lake George, where she spent the summers on the Stieglitz family compound, she took to wearing linen tunics and underskirts with a slip blouse underneath, unbelted with no corseting, as was the feminist way.

The same descriptions one might apply to O’Keeffe’s clothing in those years—soft, flowing, serpentine—could be seen in her paintings. An early abstractionist, she produced work more organic than geometric: compositions that included shells, clouds, hills, and lakes. Taking a holistic approach to her work and life, the artist was not a devotee of high fashion, but always kept her eye on it. “She wanted to look like her version of what was right and fashionable for that particular moment,” explains Corn.

O’Keeffe’s predilection for dressing on her own terms crystallized with her gradual move to New Mexico, beginning in 1929. Like many women who traveled to the region, the artist adapted a Western garb, but she made adjustments to fit her own aesthetic. In a place where the sky stretches indefinitely, it’s no surprise that blue—specifically denim—started working its way into O’Keeffe’s ensembles in the form of blouses, and, later in her life, jeans. Having come of age in an era in which well-bred women covered their heads, O’Keeffe continually adapted headwear for her own sensibility, taking to black felt vaquero hats or tying a bandanna or scarf around her head.

In many ways, New Mexico proved an ideal backdrop for O’Keeffe’s monochrome wardrobe—the adobe structures of her home in Abiquiú and the red rock cliffs of Ghost Ranch providing peach palettes in front of which her black-and-white wrap dresses sharpened. On the canvas, she traded the greens she’d used for the hills of Lake George for a palette of brighter colors, incorporating pinks, yellows, and deep blues. In portraits of the much-photographed artist, the sky empties into an unimaginable expanse behind while her slight figure, self-assured and graceful, tethers the frame. In every portrait—she sat for more than 50 photographers over her lifetime—O’Keeffe dressed only for herself, wearing the same ensemble: a black skirt suit, typically wool, evolving in cut and style with the times, and a white blouse. In this decades-spanning decision, we observe a woman in full control of her likeness. Even as her celebrity ascended—as it did beyond the art world in the late ’60s—she did little to rattle the elegant image she had worked scrupulously to create.

Is it any wonder that a woman who knew exactly how she wanted to look has endured as a symbol of modern femininity? In the decades since O’Keeffe’s passing in 1986, fashion’s pace has only accelerated and its boundaries blurred, making the prospect of a woman who dressed androgynously and refused to conform to trend cycles feel ever more prescient—and validating her instincts. “She is a symbol of independence,” Corn says of O’Keeffe’s timelessness. “Of thinking for herself and being herself in a world that might have swirled with all sorts of other possibilities or enticements to be something else.”

- Courtesy of Getty Images

- Krysta Jabczenski. Abiquiú Home and Studio, Bedroom Closet, 2019. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

- Maria Chabot. Georgia O'Keeffe, Ghost Ranch House Roof, 1944. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

- Knize. Skirt, 1964. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

- Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O'Keeffe, ca. 1921. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum