GAME CHANGERS

A behind-the-scenes look at Philadelphia’s inspiring Work to Ride program, along with four players who helped launch it to national attentionOn a quiet Monday in January, Lezlie Hiner is getting the frozen pipes fixed at Chamounix Equestrian Center. It’s the one day a week Hiner is able to do paperwork and get things in order around the stables. During the other six, the equestrian center is teeming with Philadelphian kids and young adults ages 7 through 19 playing polo, learning to ride, tending to horses, cleaning stables, studying, and generally hanging out.

That’s the way it has been for the past 25 years since Hiner founded the Work to Ride program in the stables within Philadelphia’s historic Fairmount Park. The park is located between two of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, West and North Philadelphia, which means it’s a walkable distance for the approximately 60 boys and girls in the program that may not be able to afford other transportation options, Hiner says.

Work to Ride is many things at once. It provides a place for financially need-based youth from around Philadelphia to learn how to ride and to play polo, but it also teaches them responsibility: in order to stay in the program, the kids are tasked one day a week with keeping the stables in order (they get a stipend for doing so), but not only that—they have to keep their grades up as well (in addition, Work to Ride provides after-school tutoring and summer camp scholarships). The other days of the week, when the children aren’t at school, they’re turning Work to Ride into a program that’s won a pair of National Interscholastic Championships. There are also opportunities to volunteer through the “Counselor in Training” initiative and summer employment once students are old enough.

Polo, it turns out, is a great motivator. “Some of the kids are just naturally athletic, which helps,” Hiner says. “But, as with any athlete, to be good at your craft, you have to practice. You have to put the time in.”

Despite the national titles, the program’s aims are essentially the same as the very first year, when Hiner left her corporate 9-to-5 to launch Work to Ride. “We want them to get good grades; we want to expose them to a wider world, provide them with as much opportunity as we can, and introduce them to as many new things, within our power, that we can,” she says. Adding, “It’s gone from just trying to get them through high school to, at this point, really stressing moving onto college. And that’s not going to be for everybody. We don’t groom them to be professional polo players. The polo is a vehicle.”

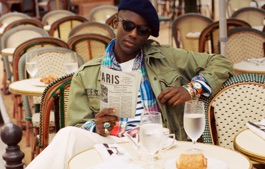

That vehicle has provided a fantastic journey for many Work to Ride alumni, including the ones featured in the Ralph Lauren men’s Work to Ride campaign, like brothers Kareem and Daymar Rosser, who have both gone on to win multiple championships and been featured on HBO’s Real Sports program, as well as Malachi Lyles, an aspiring young polo star with several All-Star nods under his belt, not to mention a modeling contract. In other words, the best proof possible that Work to Ride works. Here, four alumni tell their story.

Daymar Rosser

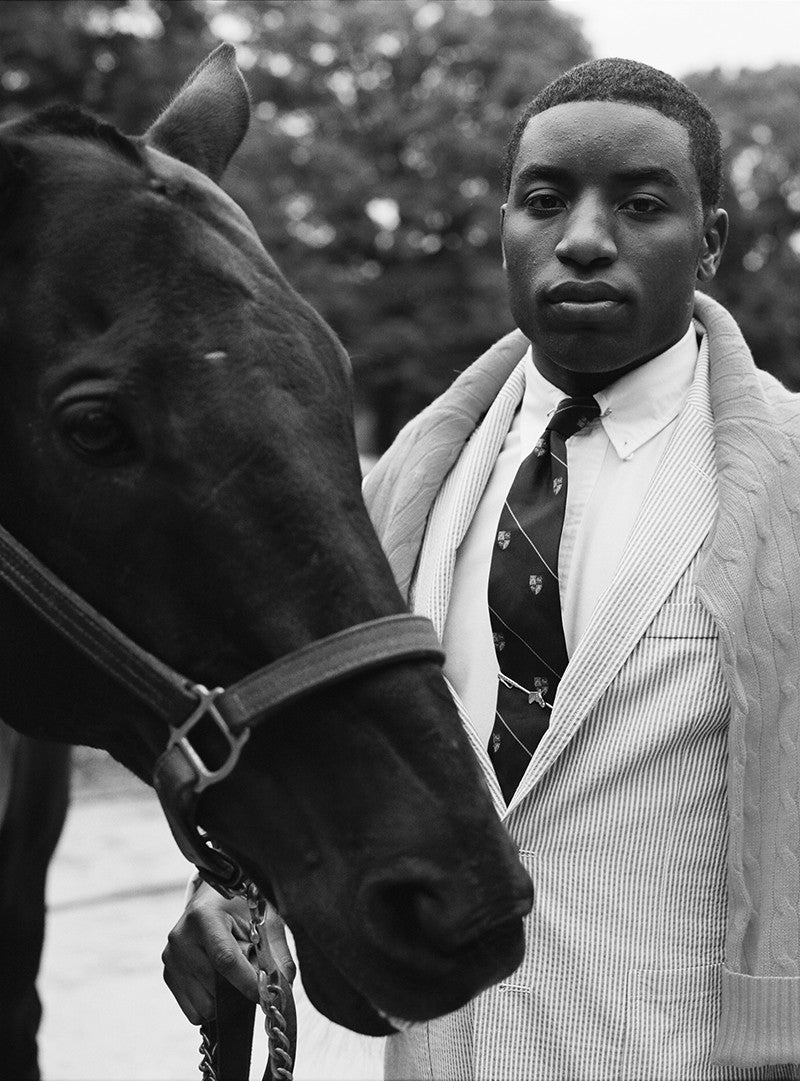

Daymar Rosser was the smallest boy on the horses when his brothers got him enrolled in the Work to Ride polo program in Philadelphia at age 5. “I was scared of how big they were,” Rosser says about the nearly 1,000-pound animals. “My brothers were like, ‘Don’t be afraid; they’re good horses.’”

He eventually got over his fear, and now, nearly 20 years later, Rosser considers himself a “horse whisperer.” That might even be an understatement. At Work to Ride, Rosser became a two-time national interscholastic champion (once with his older brother Kareem) before getting invited by a former Work to Ride teammate to help start the Roger Williams University polo team in Bristol, Rhode Island. “We were trying to get the athletic department to believe us that we play polo,” he says with a laugh. “Because, obviously, they think, ‘These black kids playing polo? That’s not going to happen.’”

It happened in a big way: Rosser captained the team to the 2017 National Intercollegiate Championship in just the program’s second year. “I’m still feeling that feeling that we had that year,” says Rosser, who now splits time between an internship at a marketing agency in Philadelphia, getting invited to pro tournaments like the 20 Goal East Coast Open at Greenwich Polo Club, in Connecticut, and working as the barn manager at Work to Ride. “Because we started from nothing and no one believed in us, and we were motivated as a team to win and put our school on the map, each and every game we were just ready to play polo.”

Kareem Rosser

Kareem Rosser is a highly decorated figure in intercollegiate polo. In 2011, when he captained the Work to Ride team (the first-ever Black/African American polo team) to the National Interscholastic Championship, he was named the Polo Training Foundation’s Polo Player of the Year. When he led Colorado State University to the National Intercollegiate Championship in 2015, he was also named the Intercollegiate Player of the Year. He was once even invited to play on Nacho Figueras’ famed BlackWatch team.

But Rosser is soft-spoken and still a little surprised that polo has taken him all around the world to places like Tianjin, China, and Kaduna, Nigeria. “A lot of polo players quote Winston Churchill, who said, ‘A polo handicap is your passport to the world,’” says Rosser. “And it really is. It’s such a global sport, and unique.”

Rosser credits Work to Ride with offering him the opportunity to develop not only as a world-class polo player but also as a person. “It allowed me to find who I truly am, and it provided alternatives that we normally wouldn’t have as kids growing up in West Philadelphia,” he says. “I think like most of the kids in our neighborhood, without Work to Ride, we would probably have fallen victim to drugs and crime.”

After graduating from CSU, Rosser returned to Philadelphia to take a job at a bank after meeting his boss, also an avid polo player. Rosser also uses his finance background to give back as the executive director of the fundraising arm Friends of Work to Ride. “I’m currently focused on launching a capital campaign and raising funds so that we can institutionalize and grow the program that we have and expand to serve more kids,” he says. “I feel like we can change more lives.”

SHARIAH HARRIS

When Shariah Harris’ mom took a wrong turn in her car one fateful day a dozen years ago and stumbled upon the Work to Ride program’s West Philadelphia horse stable, no one could have predicted Harris would become one of the most groundbreaking riders in the sport’s history. But Harris quickly took to the horses—she remembers feeling fearless even when she first began to play polo. In a male-dominated sport, she was a natural leader with undeniable skills.

It was no surprise then that after Postage Stamp Farm team owner Annabelle Garrett suffered a back injury before the prestigious Silver Cup tournament at the Greenwich Polo Club in 2017, she tapped Harris to take her spot on the team, making Harris the first-ever African American woman to play at the highest tier of US polo. “I just can’t stop thinking about it,” recounts Harris, who had been introduced to Garrett at a tournament in Argentina, but was still surprised when the call came in. “It was a big moment for me to be playing with and against the professionals that I’ve looked up to just coming into the sport,” she says. “I’ve always watched their games, but to be on the field playing with them was just mind-boggling for me.”

The resonance of the experience became even greater to Harris, who grew up in a low-income family and had never been on a horse before her mother’s fortuitous gaffe, after the match. “I saw the impact that I was having on other women of color, who were inspired by what I was doing,” she says. “People whom I had never met before came to my game to see me play in the Silver Cup. They wanted to introduce their daughters to me. It drove it home that I was doing something more than just playing the game.”

Now 21 and a junior at Cornell University, Harris is busy studying animal sciences and leading the women’s polo team to the National Intercollegiate semifinals, while also mentoring kids in the Work to Ride program. As for her big advice to young polo players? “Trust yourself and trust the horses,” she says. “It’s what I believe makes you a better player and rider—that fearless factor.”

Next year, her goal is to help the Cornell team win it all. After graduation, she plans to apply to the US Polo Association’s highly competitive Team USPA program, which mentors and trains young players and acts as a feeder program to professional polo. “Whenever I’m angry or frustrated, horses give me that extra comfort, ” she says. “I always feel at home when I’m playing.”

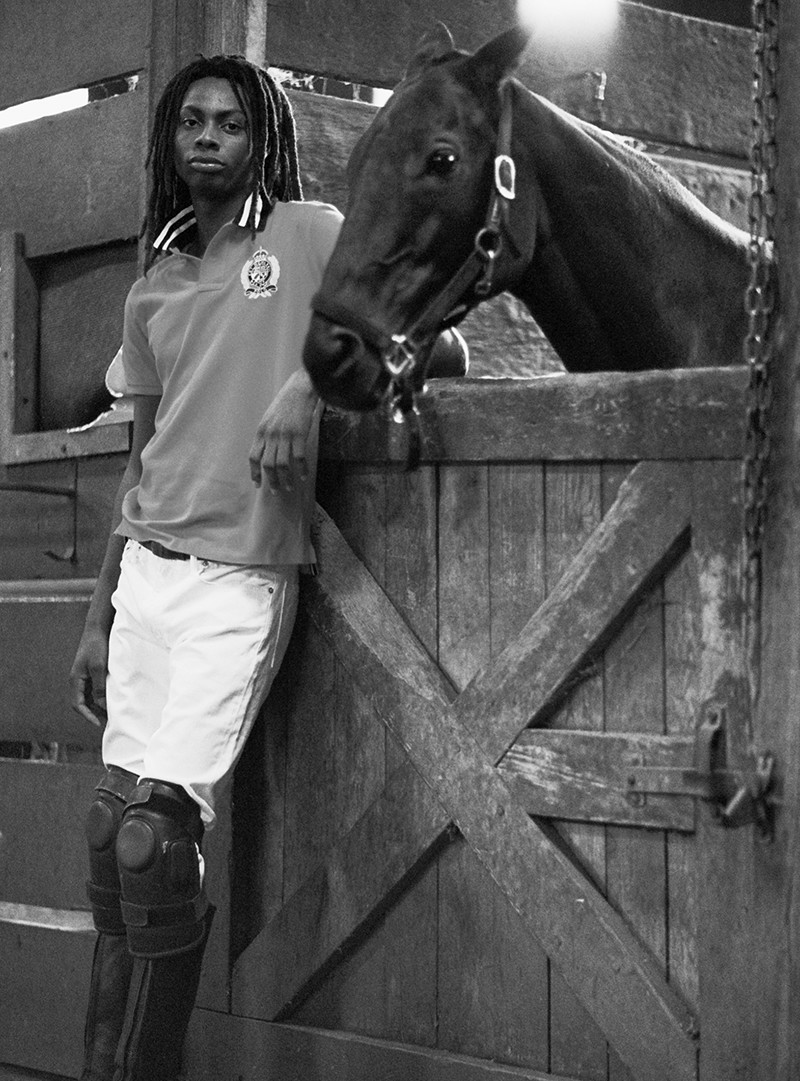

Malachi Lyles

When Malachi Lyles was 11, he had fond memories of those pay-per-ride pony attractions at the park. So his mother found Work to Ride online and enrolled him at the summer camp. Soon, he was hooked, but it wasn’t without a hiccup or two. “I remember my first or second lesson in the program, and my horse took off [at a gallop] with me, so that was a little scary,” he says. “They’re real big animals that you really don’t have much control over.”

Now, at age 18, Lyles is very comfortable around equines. He’s so comfortable, he’s considered a rising polo star, garnering a handful of All-Star selections at tournaments over the past few years. But his greatest polo achievement is getting to play with two of the best players in the world. “We went down to Wellington [Florida] last April, and we got to play with Facundo Pieres and Adolfo Cambiaso,” he says. “That’s something that I’ve dreamed about, literally.”

Lyles, who was homeschooled growing up, teaches at that same summer camp he started out in, and he’s also a working model, signed to Fetch Models. “You could literally travel the whole world playing polo,” he says. “Same thing with modeling. I want to go overseas with it and see how that goes. I want to use these two vehicles to take me as far as I can.”

The worlds collided for Lyles when Work to Ride became the face of the Ralph Lauren spring campaign. “I’d written it down in my book where I write down my goals,” he says. “Back in June of last year, I wrote, ‘I will model for Ralph Lauren,’ and the next thing you know, it’s happening.”

Ralph Lauren is proud to support the Work to Ride foundation with a grant that will directly fund collegiate scholarships for the Work to Ride high school athletes.

Learn more about Work to Ride at WorktoRide.net.

- Photographs by Scott Rudin