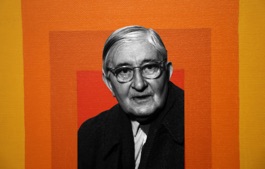

The RL Q&A: Charlie Siem

The violin virtuoso on musical heritage, the new Purple Label collection, and the enduring power of PorschesCharlie Siem is not, in fact, a race car driver; he is not a professional skier, not a clothing designer, not even a model—not exactly. These are mere sports and pastimes for the Eton- and Cambridge-educated Englishman. Siem is, actually, one of the world’s premier violin virtuosos, traveling more than 300 days a year (when he is not on the racetrack, skiing from the family chalet in Gstaad, or designing his performance ensemble on Savile Row) to perform with some of the most prestigious orchestras around the globe. But he’s also somewhat more than that. His combination of real-deal chops and pop-culture appeal (he has performed with Miley Cyrus and Lady Gaga) are turning Siem into a kind of crossover figure—introducing new audiences to classical music, while adding some debonair charm to the old concert hall.

We caught up with Siem at the Ralph Lauren Purple Label presentation in Milan recently (before he hopped in his lava orange Porsche to dash home to Monaco to celebrate his 32nd birthday with family), to talk about modern cars, antique violins, and finding freedom through discipline.

Have you been to the Palazzo before?

No, this is an absolute first—both for seeing the Purple Label collection and also the Palazzo, which is absolutely beautiful. It’s a beautiful combination of classic Ralph Lauren decoration and this really grand Milanese palazzo. And the collection, too, is classic Ralph Lauren: very military-inspired and iconic, uniform-style pieces. Very much my personal style, actually.

I think that’s absolutely right. In fact, a large part of why I was excited to go to Eton when I was 13 was because of the flamboyant uniforms [mourning attire, white tie, tailcoat]. The story is that we were dressed for the death of George III. I’ve always been a uniform person. And I still am.

Is it a bit like the Flaubert quote about being regular and ordinary in one’s life, so as to be violent and original in one’s work? Like Einstein having nine of the exact same suits in his closet, so that he didn’t have to bother with dressing choices and could be immersed in his creative endeavors all the time?

Yeah. To a certain extent, what you wear on stage is part of the performance. But actually, as much as one likes the idea of being lost in one’s emotions, and expressing what one feels in the music, to be able to effectively say something to an audience requires precision. I think about the way I dress very deeply, and every detail is so crucial to me.

I’m definitely a believer that through discipline we find freedom—rather than through throwing away discipline. Maybe it does happen to some people by chance, but in my experience, we need discipline in order to access something unique.

With classical music, and classical violin in particular, there’s such a strong, traceable legacy and a heritage. How do you see yourself fitting into that progression?

You’re spot on in terms of heritage and legacy. Because the violin is, more than anything else, a tradition. It gets handed down from teacher to student. Even the violin I play on, the physical object [a $10 million, one-of-one Guarnerius called “D’Egville” that dates to the 18th century], has been handed down by many great players that have played it before. I can link the way I play the Mendelssohn violin concerto, which was written almost 200 years ago, with the way it’s been played through those two centuries, by so many of the violinists I’ve admired, which really shrinks time down. Being part of that tradition is part of the reason I play.

The divide between modern and classical must just disappear when you’re holding an object that was made more than 200 years ago. There’s an intimacy there with the person who made it, what was played on it before.

It’s a weird thing. It eliminates the concept of time in many respects. The violin that I play on is almost 300 years old. It was made in 1735, at a time when much of the music that was being written—pre-Mozart; Bach died only 15 years later—was very light, baroque, courtly dance music. And yet we play Brahms—music that those instruments were never even designed to be able to play: that heavy-duty, rich, thick, powerful sound.

I’m tempted to draw a line from the violin to your car, particularly given how important the Porsche is to Ralph Lauren’s car collection. What drew you to the brand?

Actually, I came to it partly through a musical connection: the legendary conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan, who was a post–World War II icon. He was a unique character, very glamorous. He was a champion skier, and also an incredible race car driver. And he had a special relationship with Porsche, where they would make him individual cars, specially designed for him: the von Karajan 911. He knew so much about mechanics, and exactly what he wanted in terms of suspension, and all the technical things that I know very little about, to be honest. But he would specify to the workshop, and they would make him these von Karajan 911s every couple of years.

It’s interesting talking about such a renaissance man type of character, especially today, when we are all so specialized. You’ve said you had an almost physical attraction to music very early on, but you also seem to me very multidimensional. There’s an analogy I always use, that skills are like strings on a guitar—or violin. The more strings on your violin, the better sound you’re going to make with each of them.

Absolutely. I don’t come from a musical family, which is why I have a very broad education. It’s a balance you have to find. Being a violinist requires an incredibly narrow-minded focus on one thing. You can’t get up there and play this Tchaikovsky violin concerto well unless you spend many, many hours focused on it. The training, it’s more than you can imagine, both psychological and physical, to get up to the level that you can stand up in front of an orchestra and in front of a thousand people and play it well.

We’re talking about motor sports, and I always relate it back to what I know best—music. It’s a very apt analogy in terms of being able to step up into a high-pressure situation and get to that place where you’re living on instinct. When you’re approaching a corner, that relationship with the brakes and the throttle and steering and the kind of rhythm that you get at that high level of driving, I relate it to this process I’ve experienced through playing the violin.

As you enter into other areas, do you have any fears you won’t be able to achieve the same level of mastery you’ve achieved with the violin?

When it becomes too much of a selfish pursuit, it’s crippling. Life will become very dry really quickly. One of the biggest lessons I’m continuing to learn from going on stage is never to take anything personally. You basically throw caution to the wind. And I think that extends to everything in life—that freedom and ability to try new things, and not necessarily succeed immediately.

- Courtesy of Ralph Lauren Corporation

- Photographs by Scott Rudin; Courtesy of Ralph Lauren Corporation