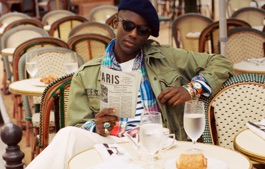

He is somehow the picture of cool. Ruggedly handsome in an offbeat way, like the star of some lost Truffaut film about cycling, with a jaunty five-panel cap, the short brim bent downward over dark sunglasses, pushing his sporty white bike through the French countryside. His face bears a hint of sideburns, a trace of stubble, and a fleshy afterthought of a nose—all of which serve his trademark mask of seriousness, a look of determination that stands in dark contrast to his sunny surroundings in the French countryside.

And then, of course, there’s that yellow jersey.

The year is 1970, and Merckx is giving a mid-race television interview, but it could be virtually any year between 1969 and 1975. Because Eddy Merckx sported that prestigious golden shirt—famously worn by the active leader of the Tour de France—more times (96) than any other racer in history, a mark that mirrors his 34 all-time stage wins and record five Tour victories. He is almost certainly the greatest cyclist of all time and decidedly the greatest of his time, an era before systematic chemical enhancement put a big asterisk on everything. “In our time we were professionals with the hearts of amateurs,” he once said. “Now they are professionals with the hearts of professionals.“

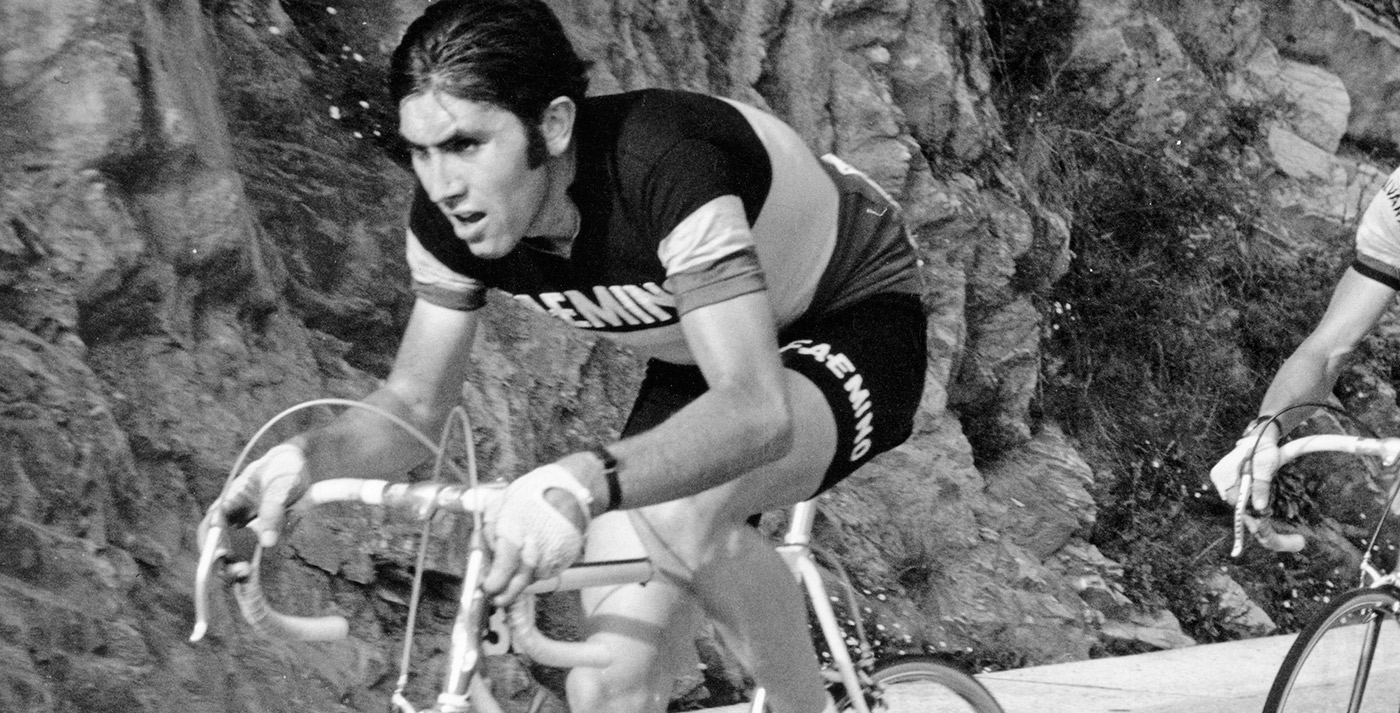

He was an relentless cyclist whose dedication earned him the nickname The Cannibal. Whereas his rivals often paced themselves according to the rigors of the course (and, per longstanding cycling etiquette, permitted other riders to claim stage victories, so long as their overall lead was not threatened), Merckx raced all-out from start to finish. Like Babe Ruth or Michael Jordan, Merckx didn’t just dominate his sport, he fundamentally transformed it, leapfrogging into the future and setting records that stood for decades.Still, it’s a nom de sport that never quite fit right. Far from a villain, he was a hero, a man who directed his fiercest criticisms inward. “I like winning,” he told an interviewer in the midst of the 1970 Tour de France, en route to his second of four straight victories. “I think I have the right to be hard on myself and on others.”

His story begins in 1945, in a small town in Belgium. Born Edouard Louis Joseph Merckx, the son of a grocer, he began to ride for reasons that still seem to escape him decades later. “Cycling is a passion,” he told one recent interviewer. “Since I was a kid I always dreamed of being a cyclist—in the school holidays I would play Tour de France outside. Why? No one in my family was a cyclist. Why do some people become priests?…I just wanted to be a cyclist, and why I didn’t know.”

Whatever the reason, he quickly excelled, winning the Amateur World Championship Road Race at age 19. He turned pro the next year, where (again) he excelled, capturing the prestigious Milan-San Remo title in 1966. It was an auspicious start to an incomparable career. He would go on to win an astonishing 35 percent of his more than 1,400 career races.

He was especially tenacious in big races, and his litany of accomplishments is like none before or since: the aforementioned five Tour titles; five Giro d’Italia victories; and a record 19 victories in cycling’s so-called five monuments (Milan-San Remo, Tour of Flanders, Paris-Roubaix, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, Tour of Lombardy), winning each of them at least twice. The final tally? A record 525 victories, including 445 as a pro. That record is considered as out-of-reach as, say, Wayne Gretzky’s 2,857 career points in the NHL, or Cy Young’s 511 career victories in baseball.

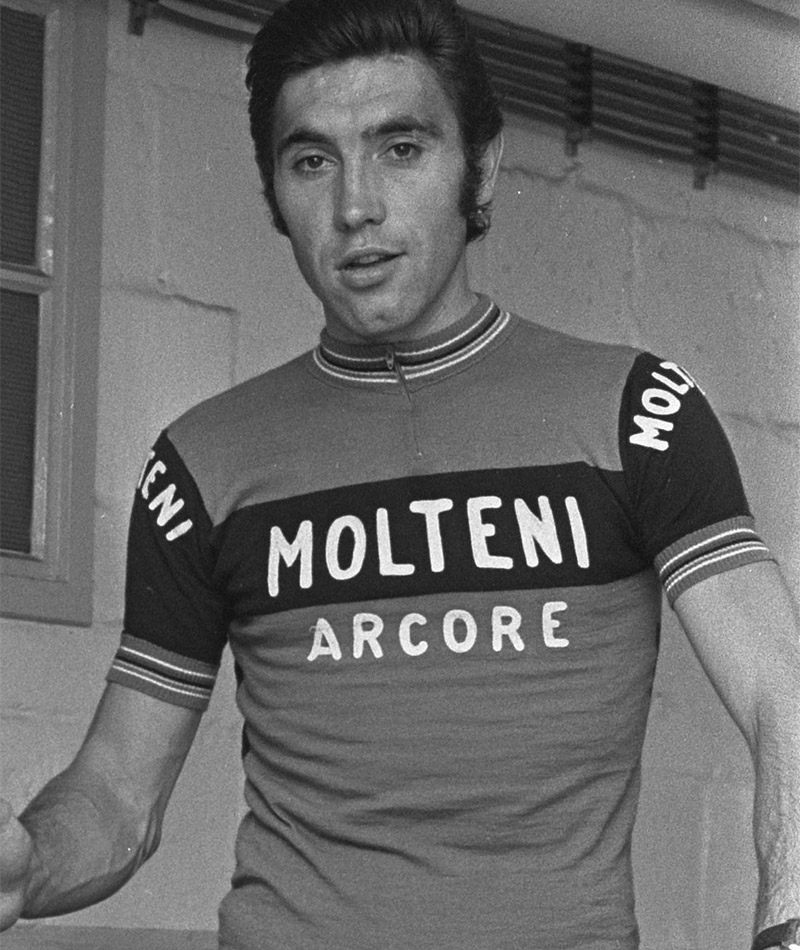

And he did it all before retiring in 1978 at the ripe old age of 32. He won with such a no-nonsense manner that struck some as inscrutable, even aloof. That coolness also lent him a hint of glamour, particularly in the red-and-white Faema or burnt orange Molteni jerseys he wore on those rare occasions he wasn’t in yellow.His career wasn’t without its lows. In 1969, during a derny race (essentially, a track race where cyclists are paired with pace riders on motorized bikes), a rival cyclist crashed in front of him, causing Merckx and his pacer to wipe out as well. The incident left him concussed with a cracked vertebrae and a twisted pelvis. Even worse, his pace driver was killed immediately. Merckx said he was never the same afterward. (Even if some of his greatest successes were still ahead.)

But he always carried himself with great dignity. In the midst of the 1971 Tour, he trailed one of the better racers of his generation, Luis Ocuña, by more than seven minutes. During the 14th Stage, Ocuña crashed, ultimately leaving the race. The next day, Merckx declined to wear the yellow jersey out of respect for his fallen rival. The gesture revealed the true heart of the supposed Cannibal.

Today, 40 years later, he has his own line of bicycles and remains an active cyclist, participating in benefit races (and rides to the café with some of his former competitors). Ever the racer, he adheres to a philosophy of not looking back. “I’m not too nostalgic,” he said recently. “I remember what it was like to be 15 and wanting to become a pro cyclist. It was a really nice time in my life. But it’s gone.” And yet, the man—and his legend—remains.- Photograph by Michel Ginfray/Sygma via Getty Images

- Dutch Nationaal Archief